Some art changes how we see the world. It catalyzes our politics or broadens our ambition, imparts empathy or disillusionment. But some art changes how we see ourselves. For certain listeners, hearing the Blue Nile for the first time activates a part of your brain that exists beyond language and between emotions. It’s the same part that fills in the source of pain between the lines of a Raymond Carver story or maps the road from season’s greetings to profound melancholy in Vince Guaraldi’s Peanuts music. In a Blue Nile song, you sense the lonesome silence beneath the buzz of city life; the unnavigable distance between long-term partners; the acknowledgement that love and loss, life and death, success and failure are forever part of the same cycle.

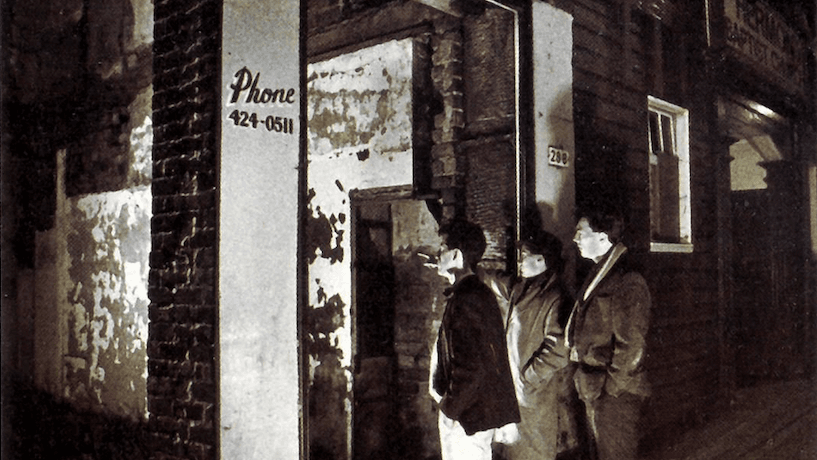

“These are the moments we live for,” vocalist Paul Buchanan said in 1989. “The moments that sustain you during the more humdrum aspects of what we do. Maybe it’s the middle of the night and you look at your husband, your wife, and you know that you love them.” With his multi-instrumentalist bandmates, PJ Moore and co-songwriter Robert Bell, Buchanan zooms into these exchanges to prolong them or dissembles them into jagged pieces that leave the bigger picture to us. Set almost ubiquitously in their native Glasgow, their songs sparkle with a sense of place but offer just enough space to get lost.

No score yet, be the first to add.

In the opening title track of their 1984 debut, A Walk Across the Rooftops, the Blue Nile present a bird’s-eye view of their journey. In a stately baritone that occasionally loses its composure as a strained bellow, Buchanan guides us through the grayscale skyline, the redstone buildings, the tower of St. Stephen’s Church. Surveying the landscape of his hometown and backed by the Scottish National Orchestra, he introduces himself with a vow. “I am in love/I am in love with you,” goes the chorus, simple words complicated and made real by the creeping, slow-building arrangement. It is the stop-start sound of an identity forming, like those graphics that fill in your fingerprint as you bring your finger up and down repeatedly.

The song begins with the faint sound of a synthesizer, like a passing siren they’re waiting to fade from earshot. This choice establishes a sense of dynamics that means casual listening is more or less off the table. But it also means that, once you’re tuned in, your participation becomes an active component in bringing their music to life. Inspired by 20th-century composers like Bartók and Britten, the Blue Nile consciously avoid the traditional pop song structures in favor of patient swells of intensity. They extend upward like urban architecture; they begin with a murmur and end with ecstatic refrains; they keep steady time with a drum machine and favor chord progressions that take a while to resolve, if they ever do, leaving you in constant, snowballing anticipation.

For a band that has spent so much of its career in relative obscurity, the Blue Nile have had disproportionate brushes with fame. In 1984, Bono named A Walk Across the Rooftops his album of the year; in 2024, Taylor Swift mentioned them in a lyric. They’ve been covered by Rod Stewart, Isaac Hayes, and Rickie Lee Jones; cited as an influence by should-have-been peers like Phil Collins, Peter Gabriel, and Tears for Fears. In the early ’90s, Robbie Robertson invited them to record a song and hopefully lend some of their magic to one of his solo albums. “And then,” he said, “like ghosts they went back to Scotland and I never heard from them or saw them again.”