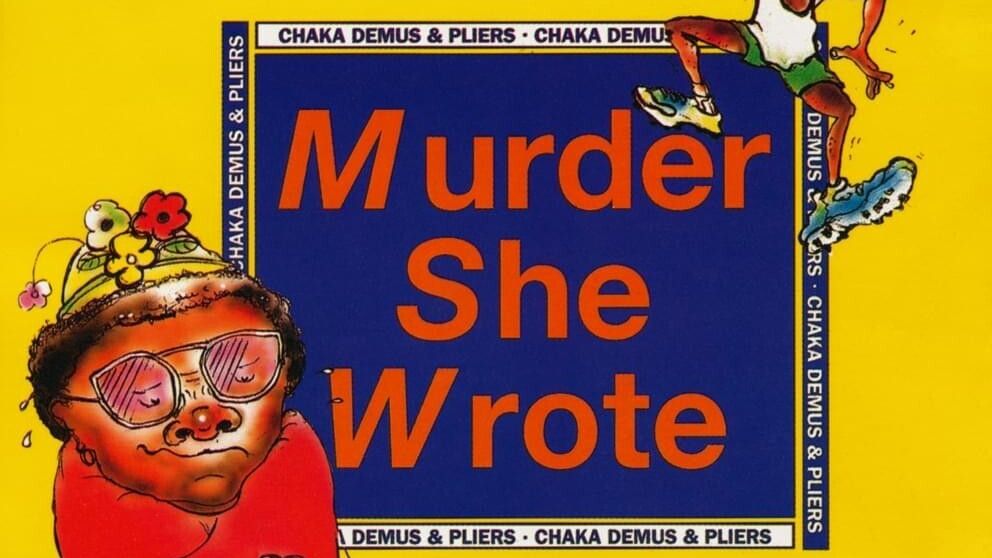

Certain rhythms are so striking that you can recall the exact time and place they first demanded your full attention, a timestamp encoded in neck and hip muscles. But the rhythm track of Chaka Demus & Pliers’ “Murder She Wrote” is so distinctive that the opposite is true, its music somehow seeming to exist outside of time even as the Jamaican dancehall hit became a global phenomenon. The beat of “Murder She Wrote”—often called the “Bam Bam” riddim, after another Pliers tune sung on the same backing track—flows so naturally that it bypasses muscle memory and goes straight to the brain’s pleasure centers. Like oxytocin, the “Bam Bam” pattern triggers an amnesiac effect, erasing the memory of previous listens and encouraging the body to accept it again, thereby ensuring the survival of the species.

The neurochemical keys to this process are encoded in the song’s serpentine groove, a hypnotic inside-out drum pattern that’s difficult to resist and seemingly impossible for anyone but the late icon Sly Dunbar—who passed away this week at 73—to play accurately. As anyone who’s attempted to tap it out can attest, the snare seems to fall on every beat except the one you’re currently focused on, leaving the track anchored, in defiance of gravity, by atmospheric shakers and and the layered guitarwork of Dunbar’s Taxi Gang collaborator Lloyd “Gitsy” Willis: one layer an urgent Morse code pulse of rhythm guitar, the other a five-note ostinato worthy of a psychedelic cumbia. Somehow these sparse ingredients provide the perfect complement to the commanding bark of veteran dancehall deejay Chaka Demus (“Step up, my youth: Hear this!”) and the sweet melodic tone of singjay Pliers, all but guaranteeing the combination would grow into a worldwide hit. The rhythm’s uncanny lethean qualities would eventually stick to dozens, if not hundreds, of other vocals, making new hits time and again.

This seemingly timeless rhythm was born of a particular historical moment. It represented the peak of an early 1990s wave in dancehall, now remembered as a golden era both in creativity and cultural impact that resulted in major label deals and MTV airplay for artists like Shabba Ranks, and Patra. More importantly, it represented a moment of rapprochement in the musical conversation between Jamaica and the rest of the world, one over which Dunbar was, in some ways, singularly prepared to preside.

Cutting his teeth as a teen on early reggae sessions produced by Ansell Collins (“Double Barrel”), Lowell Fillmore Dunbar earned the nickname Sly via his predilection for Sly and the Family Stone covers while drumming for Skin, Flesh & Bones, the house band at Kingston nightclub Tit for Tat. To keep a full dancefloor, the gig required mastery of calypso, soul, funk, and early disco grooves, as well as reggae, and young Sly could do it all. Musicians from another club called Evil People, three doors down on Red Hills Road, would regularly come by on their break to check for the prodigious drummer.