When he was a young child, Richard D. James loved to crack open the family piano and detune the strings he found inside. He wasn’t after music, exactly. He didn’t really know what music was yet. His family had minimal interest in it, which fixes James’ childhood at a rather specific historical cusp, when people lukewarm on music would still have a piano around as a matter of course. Instead of piecing together tunes, he found himself captivated by the materiality and mechanics of sound itself. There in his Cornwall home was an intricate machine many times his size, designed to do nothing but produce note after note after note. A finger pressed a key and a tone reverberated. He could look inside the device and he could fiddle with it and he could change how it worked. A string loosened and a pitch bowed. Hammers tapped slackening fibers and instead of the pleasant overtones of a major scale, a nauseating cacophony swelled from the instrument’s wooden belly. His parents hardly encouraged these experiments, but neither did they forbid them. “I just got shoved in a corner of the house and was allowed to get on with it,” James said in 1994.

Soon the piano was not enough. James took to prying open electronic keyboards and bending their circuits when their built-in parameters didn’t satisfy his hunger for noise. Once he pressed against the limits of what prefab machines could give him, he started building his own synthesizers. He played around with tape recording and produced tracks compulsively; the earliest cuts on the first volume of his Selected Ambient Works he made in the mid ’80s, when he was still in his early teens. In time, music found him: Acid house, techno, trance, and jungle all filtered through as they coursed across the United Kingdom, Europe, and the globe. Subtler stuff from earlier in the century drifted in, too: ambient, musique concrete, avant-garde. Most of it chafed at him but he internalized its structures all the same. As his childhood rolled to a close, he started cutting tracks that took flight on local dancefloors. An early hit, “Didgeridoo,” was so named because that’s what ravers would chant when they clamored for him to play it. He found an audience in UK raves and detested performing for them. For James, bliss didn’t pour through the release of a riotous crowd but crept in total solitude as he pounded out track after track, late into the night—making, making, making.

No score yet, be the first to add.

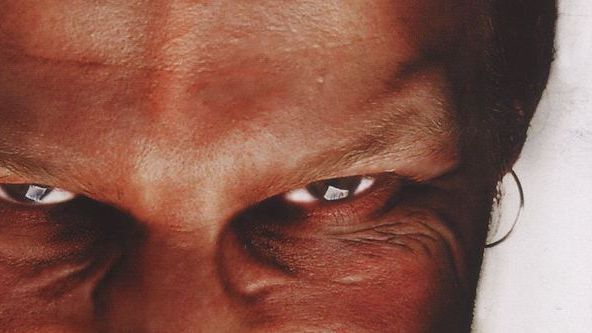

If James bristled at the prospect of public exposure early in his career, he at least seemed to enjoy concocting his own mythologies. Reporters lapped up the stories of the prepared piano that the young James stumbled into by sheer intuition, never having caught wind of John Cage. They christened him the Mozart of 1990s techno, and James countered by saying he’d never heard Mozart in his life. He drove a tank around England, claimed to live in a bank vault, spent long hours playing city-sim computer games on acid, and weaned himself down to just two hours of sleep a night so he could have more time to work. He trained himself to lucid dream so he could write songs in his sleep. He adorned the covers of his albums with his own demonic grin. Then, since industry standards stipulated he had to perform live every now and then, he spilled the spectacle onto the stage. He dropped a turntable stylus onto a disc of sandpaper and let it spin for minutes on end, then encored with a kitchen mixer fed into a microphone. He invited bodybuilders and teddy bears to dance for him while he lay on his stomach, twiddling knobs, kicking his feet behind him like a child on his bedroom floor.