Daniel Lopatin doesn’t score the Safdie brothers’ movies so much as open portals in them. In Good Time and Uncut Gems, his worship of all things kosmische created a peculiar contrast with the images on screen, drenching the brothers’ grainy tales of ’10s debauchery in the aura of an earlier time. Hospital hallways gleam with the same twilit aura of Thief; New York’s diamond district ripples with as much danger as the landscapes of Sorcerer. Lopatin isn’t recreating Blade Runner with his soundtracks as much as Risky Business, pulling us into the subconscious of the Safdies’ manic characters and submerging us in their doomed self-sabotage. When Howard Ratner hits, we don’t just resolve to a major chord—we enter the realm of the angels, with glowy flutes and Mellotrons dancing in the air like a thousand roses blooming at once.

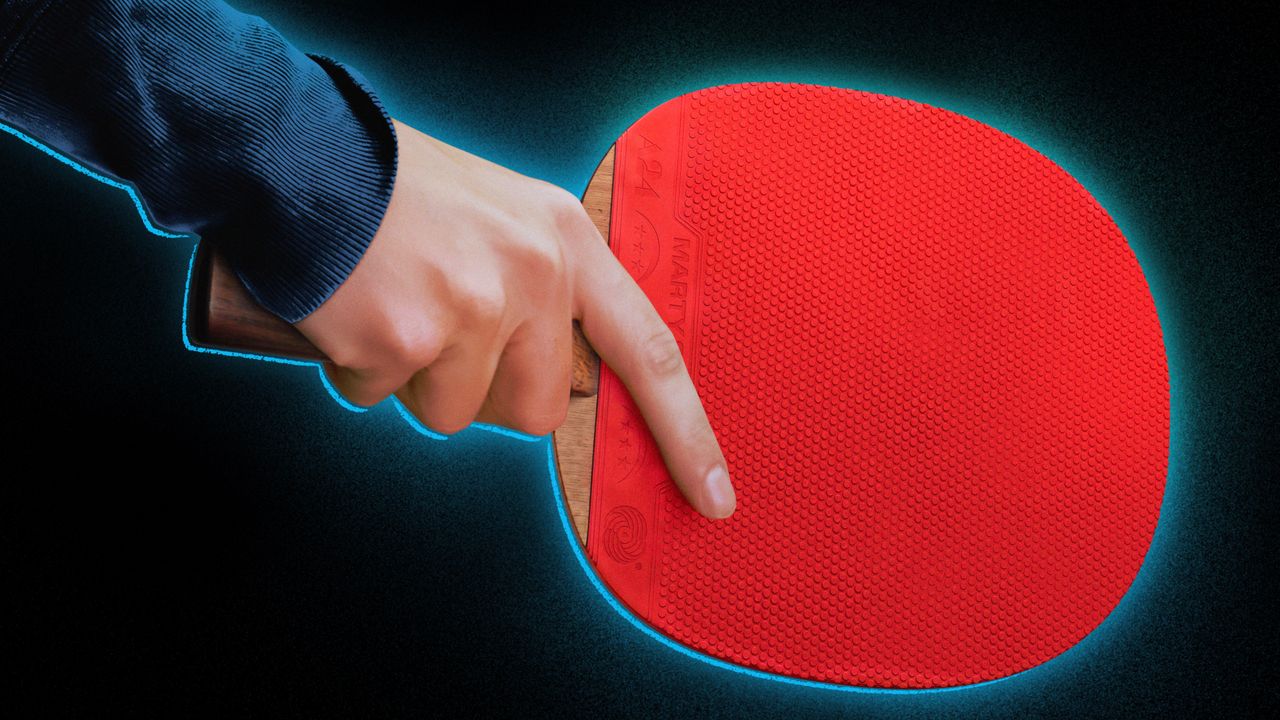

It’s all very heightened, absurd even. But with his score for Josh Safdie’s whirlwind new Timothée Chalamet vehicle Marty Supreme, Lopatin has taken this woozy, internalizing effect and sent it outward. Safdie’s latest follows a hungry young Jewish table tennis player in the early ’50s on his mission to bring glory to himself, his game, and all of America while he’s at it. As Chalamet hurtles toward his supposed destiny, a parade of ’80s hits lights the way, pointing toward some imagined time as futuristic for him as it is nostalgic for us. Tears for Fears’ “Change” launches the film like it’s shooting Marty out of a cannon. Songs by Peter Gabriel and New Order swirl as if we were caught in an endless training montage. I won’t spoil how Alphaville’s “Forever Young” gets used, but it underscores a particularly seminal moment for our hero.