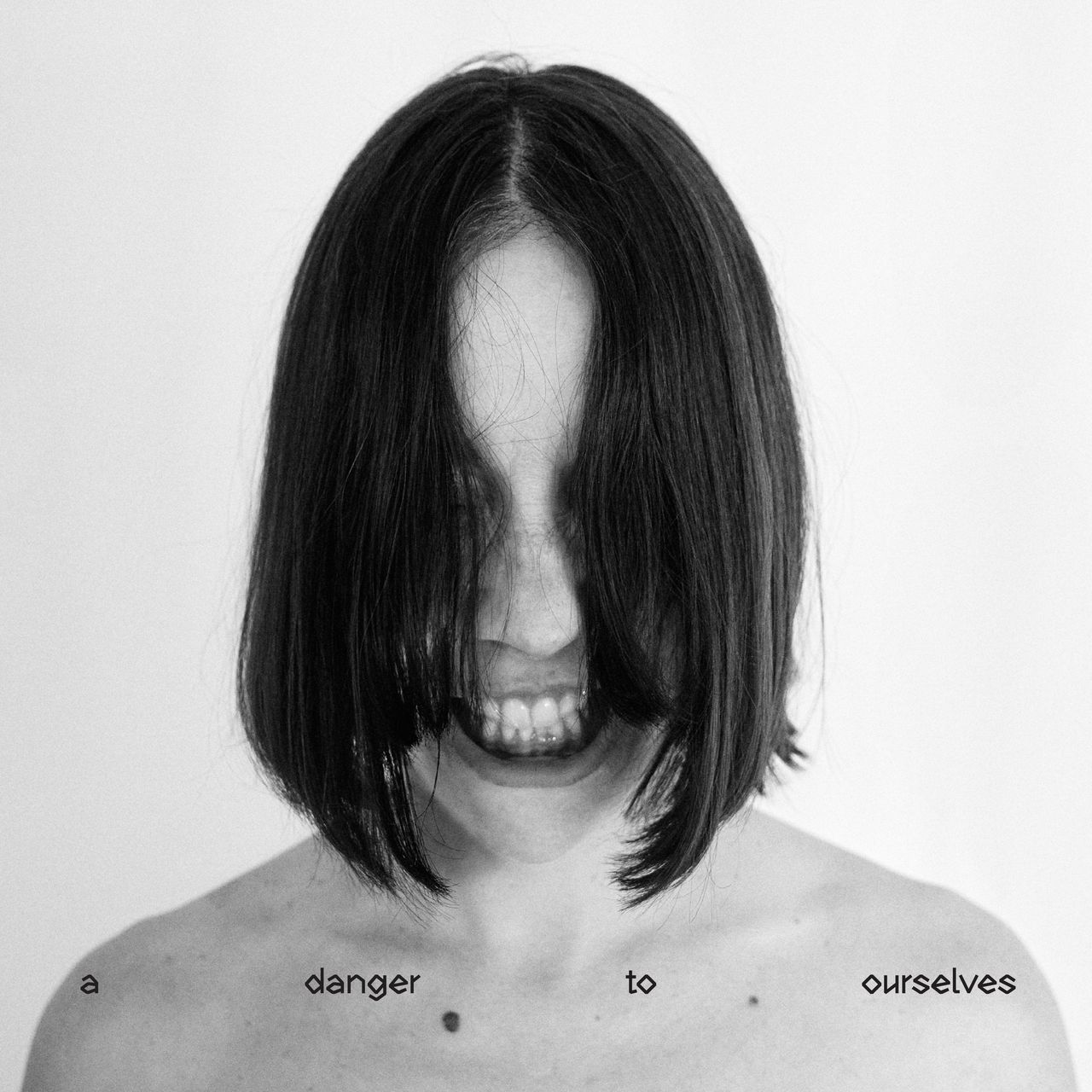

On July 7, 2025, Lucrecia Dalt’s heart stopped. She had suffered a severe epileptic seizure, and eight seconds would pass before it resumed beating. The next day, the Colombian musician released “caes,” the third single from her breathtaking new album A Danger to Ourselves—a song that suggests, she says, “that the sublime can be reached through surrendering to the act of falling.” For two days after her near-death experience, she soared, so overwhelmed by the beauty of her surroundings that she wondered if she had actually died and was experiencing the afterlife. She hadn’t, of course, and the world that wowed her was the same one she occupied before her heart had stopped. She had just surrendered to the fall.

“Caes,” a gorgeously harmonic duet with Amor Muere’s Camille Mandoki, draws inspiration from the Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta and the model Evelyn McHale, two women whose fatal falls remain intertwined with the artworks connected to them. McHale’s final photograph, “The Most Beautiful Suicide,” was taken by Robert Wiles and repurposed by Andy Warhol, while Mendieta’s haunting multimedia series Siluetas presaged her tragic end. Dalt’s tumble was decidedly more metaphorical; after years on the road, juggling multiple projects while touring the world, she moved to New Mexico and fell in love.

The path of Lucrecia Dalt’s career over the past 20 years has been serpentine, growing from electronic-tinged synth pop into various sonic abstractions, embodying beasts, spirits, and the earth itself before reimagining the boleros of her youth through the lens of science fiction. Each experiment felt distinct, yet they all shared a similar detachment; building her records around fantastical characters and surrealistic concepts, she maintained a semblance of distance between her art and her personal life. Her latest work obliterates that gap.

Most of A Danger to Ourselves was written and recorded in New Mexico at the home studio of her partner, David Sylvian, the veteran British art-rocker, and its content captures the intense exchange of new love. Dalt says the record emerged after “spending enough time in the abyssal realm of erotic delirium.” This time, rather than invoking mythical creatures, she says, “the lyrics function as declarations, or odes, and the most personal truths I have explored to date are found within those lines.” It’s the most exposed she’s ever been on record.

The album opens with their duet “cosa rara,” a deceptively buoyant investigation of lust built upon dynamic drum loops from Alex Lázaro, who also gave ¡Ay! its rhythmic backbone, that shrink and expand, building and releasing tension. The new lovers swirl around one another amid breathy harmonies, scattered flexatone, and the screech of Sylvian’s guitar. Enveloped by their own desire, they succumb to it, their minds and bodies disassembled and rearranged. The climax is a car crash; Sylvian’s gravelly baritone narrates the final, refractory verse with post-coital clarity, the bliss of surrender tempered by unease.