When Anna Domino moved to New York City in 1977, she thought she was witnessing its death. “It was the summer of the garbage strike, transit strike, Son of Sam serial killer and the blackout and riots that followed,” she told PopMatters in 2013. “The city was bankrupt and half in ruin … The streets were empty at night except for stray dogs. It was a wilderness and we all found each other and huddled together for warmth and food, which was scarce and not very good. We all wanted to do everything and of course we did.”

Domino was shy and she was a hustler. The apartment buildings were dank and distressed—many were targeted for arson by landlords in search of insurance payments—so she learned how to fix wiring and install boilers. She found work in the dingy sweatshops that had cropped up in the city in the preceding years, fixed up old apartments for cash in her free time and, at night, went to the Mudd Club and Max’s Kansas City, rubbed shoulders with “bored and self-conscious” painters, dated Basquiat for a little while.

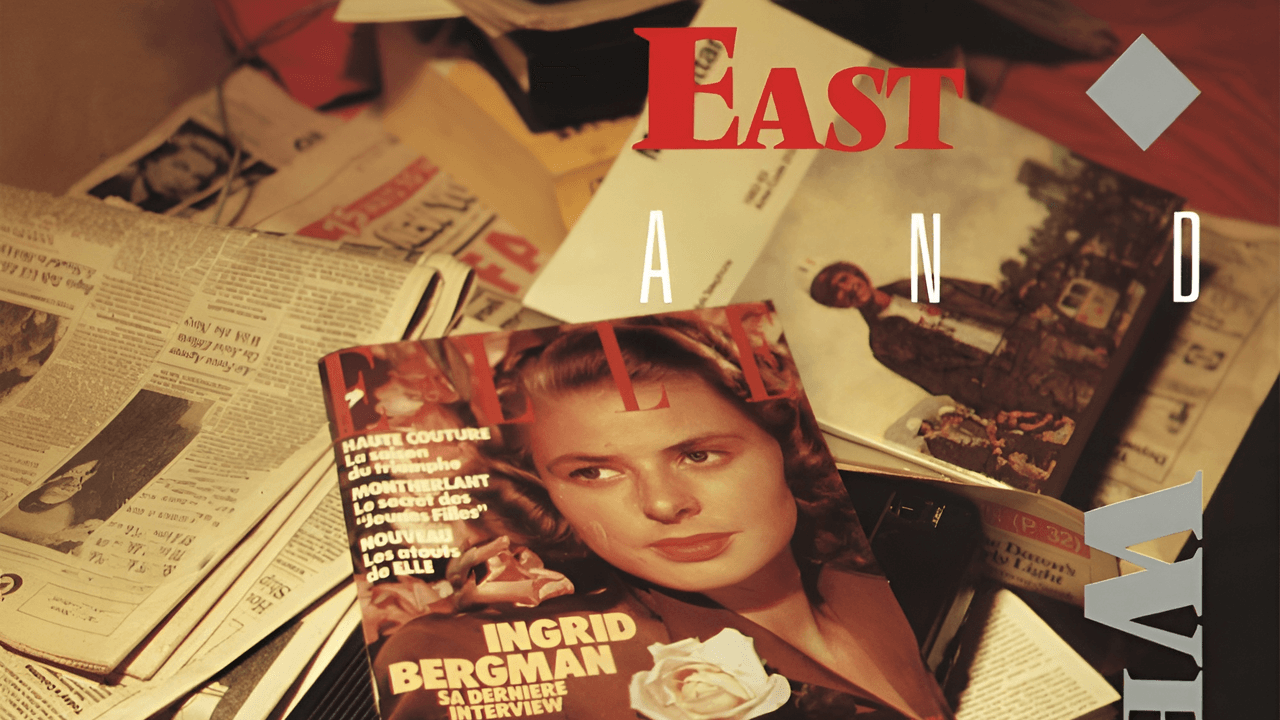

She renovated a storefront on East 10th Street and lived in it for a period, then charged the next tenants a fee for the repairs she’d made. She used the money to buy a cassette recorder, with which she made demos for East and West, her debut album. Her songs—staunch, curious, seemingly drawn from the luminous zone between dreams—made loneliness sound like an art form, perhaps tapping into memories of a childhood spent moving from place to place with her family. Domino’s music might as well have been recorded by the last woman on Earth: She’s the queen of a scene of one, strutting through a Manhattan “lit by small fires, stuffed with urgent clues” to a stark, potent pop soundtrack.

Released in 1984, East and West is the Velvet Underground & Nico of avant-pop: Not every aspiring It Girl heard it, but every one who did was inspired to pick up a TEAC cassette deck and a microphone. Domino’s resolute, searching voice is the clearest antecedent to the sound of musicians like Astrid Sonne, Carla dal Forno, Molly Nilsson, and HTRK’s Jonnine Standish, whose intimate transmissions feel both dissociated and liberated. Now, Domino’s voice is all over NTS Radio, literally and spiritually: Her plainspoken vocals and blend of post-punk, programmed drums, and louche jazz are an enduring archetype for artists whose interest in pop starts and ends with its immediacy.