Some musical discoveries function like a subway station: They become hubs for vibrant lines connecting clubs, lofts, and basement studios. Others are like stalls in a bustling marketplace, or a popped trunk in a parking lot, promising the best of the block.

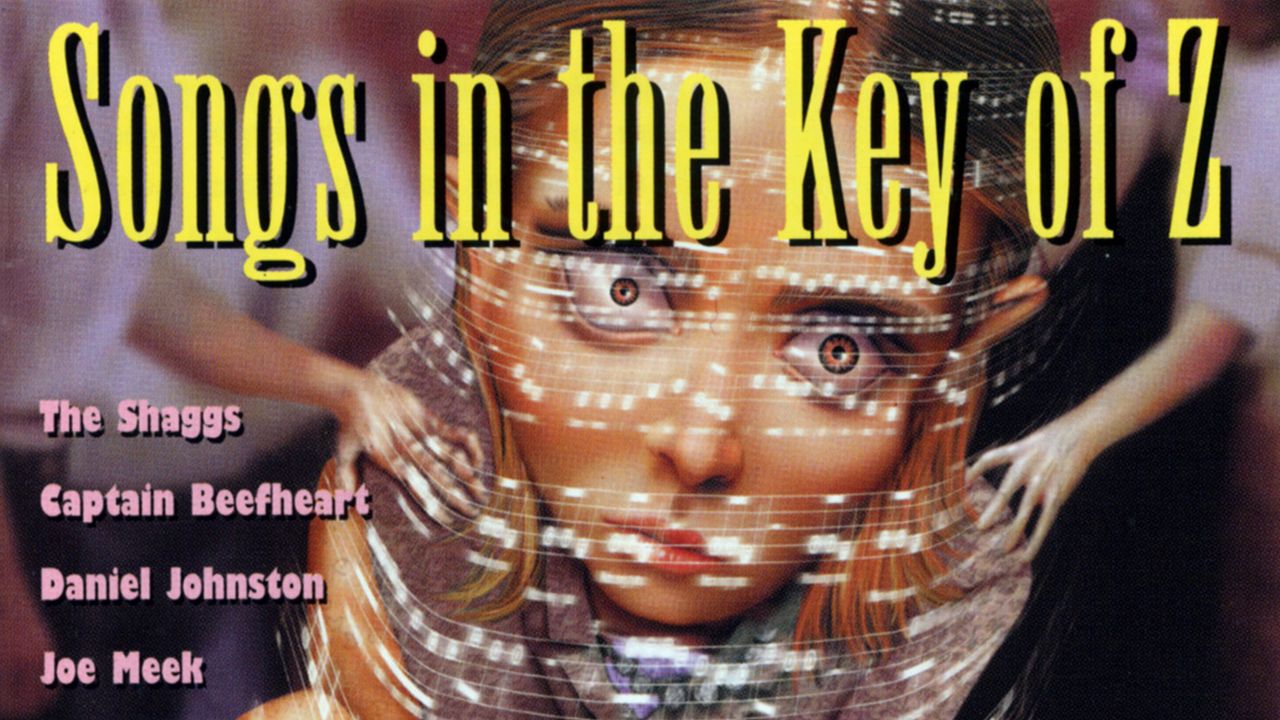

But there is a type of music that’s a dead end. You can’t easily connect it to a scene or a label. It’s not some treasure to be imparted—you hand it to someone like a furtive cigarette. There’s no romance, no mystery other than how it got recorded. It may be unclear who the music was ever for, but it’s against seemingly everything: lyricism, artistic remove, conventional rhythmic sense. For most people, that kind of art prompts a quick jab at the stop button and dark thoughts about delusion or mental illness. For a select few, it represents the last frontier of musical expression.

For decades, author, producer, and archivist Irwin Chusid has been patrolling that frontier with X-ray spex and a ray gun. A self-described “connoisseur of marginalia,” Chusid has been a DJ on New Jersey’s legendary freeform radio station WFMU since 1975. In the early ’90s, he was scraping by on freelance writing and producing albums: at one point, his parents were loaning him $50 a month so he could eat. His fortunes shifted when Bar/None Records asked him for a reissue pitch, and he suggested the experimental big-band producer Juan Garcia Esquivel. 1994’s Space-Age Bachelor Pad Music—like the Stereolab EP from the year prior, named after a phrase coined by animator and exotica collector Byron Werner in the 1970s—sold a shocking 70,000 copies, helping move the lounge revival mainstream.

Chusid’s other work during the decade (reissues of forgotten bandleader and electronic-music pioneer Raymond Scott, liner notes for Rhino’s Golden Throats series of singing celebrities, producing R. Stevie Moore) showed someone able to make a meal out of bygone (or bad) tastes. But it was a little-noticed reissue of a laughably obscure 1969 album that changed Chusid’s destiny: Into Outer Space with Lucia Pamela. Chusid first heard Into Outer Space in 1984, when a WFMU listener mailed him a homemade tape. It took him four years to obtain an original copy, and another three before he got it released on Boston’s Arf! Arf! label.

Lucia Pamela was a bon vivant and lifelong entertainer. In 1926, she was named Miss St. Louis; in the ’30s and ’40s, she led the all-women big band Lucia Pamela and the Musical Pirates. After the group disbanded, she reportedly played accordion for Lionel Hampton and Paul Whiteman; she also performed at USO shows with her daughter Georgia, billed as the Pamela Sisters. When Lucia was 65, she recorded her only album, a zany, jazzy romp that she would insist was recorded on the moon. According to legend, she played every instrument, but it’s also possible she kidnapped a Dixieland combo at gunpoint. The prevailing spirit is that of a public-access kids’ show running on fumes and flopsweat; her voice is all brass and zero polish. In college, I found that the 90-second closing track “In the Year 2,000!” was the perfect way to pad a mix CD’s runtime. “We’ll even play football too, on the year 2000!” she hollers. (In January 2000, as it happens, the St. Louis Rams won their first Super Bowl. The team’s owner was Georgia Frontiere, Lucia Pamela’s daughter.)