There comes a time when devotees of Bruce Springsteen start obsessing over the music he didn’t release. Once you’ve made it through the studio albums and B-sides, the live records and bootlegs, you’ll hear rumors of all the music left in a vault somewhere in the swamps of Jersey—casualties of a dogged perfectionism that led the endlessly prolific songwriter to consider scrapping even Born to Run and leaving “No Surrender” off Born in the U.S.A.

At this point in your fandom, you may decide that disc two of Tracks—1998’s four-disc, career-spanning outtakes collection that still managed to disappoint some fans for not being comprehensive enough—is the best record he ever made. You may go to a concert holding up a sign to hear “Zero and Blind Terry.” You may insist there’s a scrapped album from the ’90s inspired by West Coast hip-hop—and that it might finally be coming out soon. Friends and family might start to worry about you.

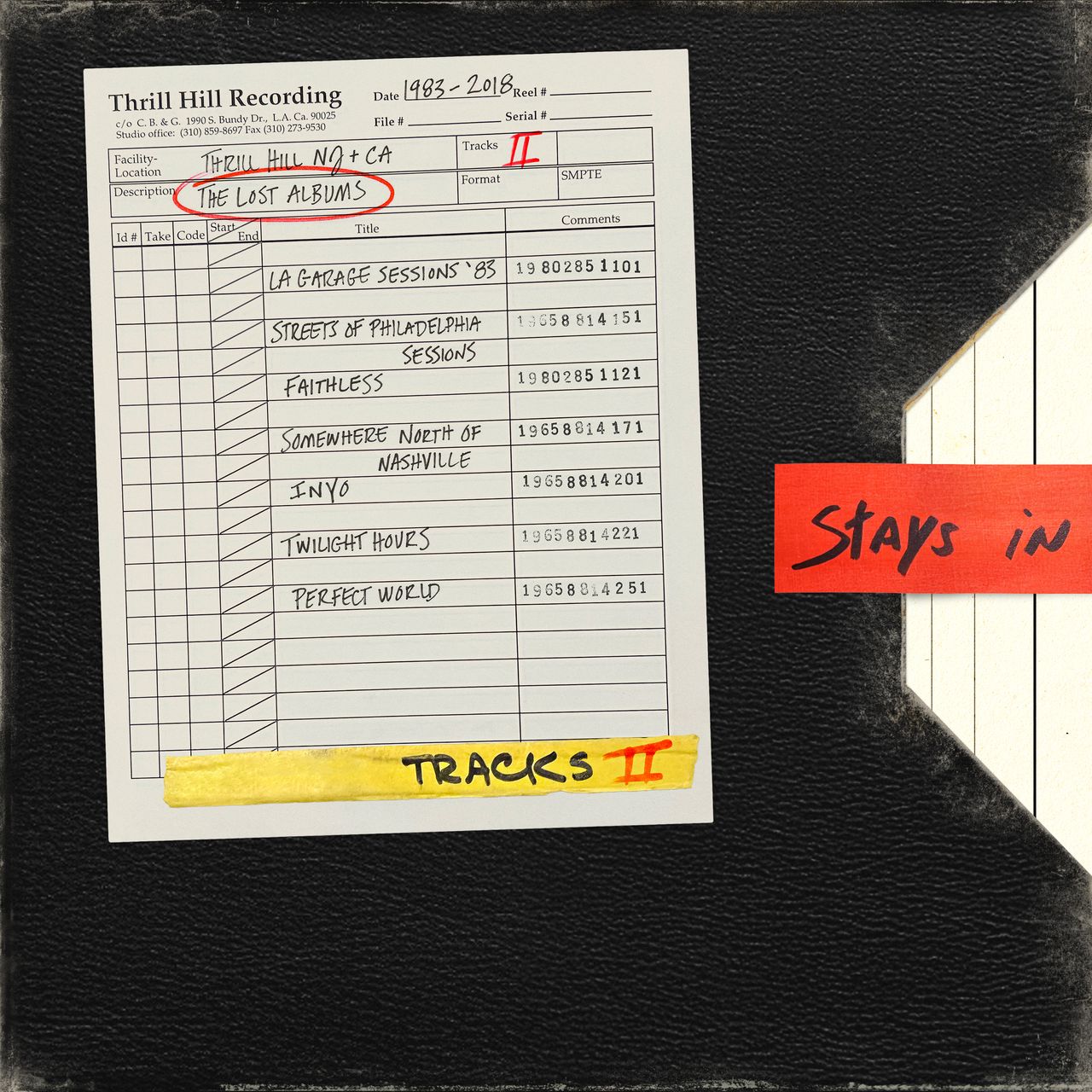

While I understand this all could sound fanatical, no one has perpetuated the mythology more than Springsteen himself. With this review of Tracks II: The Lost Albums, I’ve now covered 11 official releases for this website, and by the time that pretty much all of them were published, he was already in the press talking about the next thing he was working on. (The streak continues: Tracks III is finished. As is a new solo album.) Even given this history, Tracks II holds a special place for Springsteen fans. Where Tracks compiled individual songs that were cut from his famously exacting studio albums, the long-awaited sequel presents entire projects that he wrote, recorded, and, for one reason or another, decided not to release. Some songs have been passed around in rough form for decades; most are unknown to even the most serious collectors.

Before we get to the music—seven previously unreleased albums recorded between 1983 and 2019, 83 songs, the majority of them excellent—it’s important to situate Springsteen as a legacy artist in 2025. Where Bob Dylan continues his Bootleg Series in the form of expertly crafted museum exhibitions, and Neil Young opens his Archive as an ever-expanding garage sale where the mess is part of the charm, Springsteen engages with his past in the present tense. These days, it’s not uncommon for him to write belated lyrics to a vintage instrumental, or revisit 50-year-old songs for a brand new record, or place his 1987 outtake “The Wish” as the emotional centerpiece of his autobiographical Broadway show. “I always picture it as a car,” he explained of his body of work—and what else. “All your selves are in it. And a new self can get in, but the old selves can’t ever get out. The important thing is, who’s got their hands on the wheel at any given moment?”