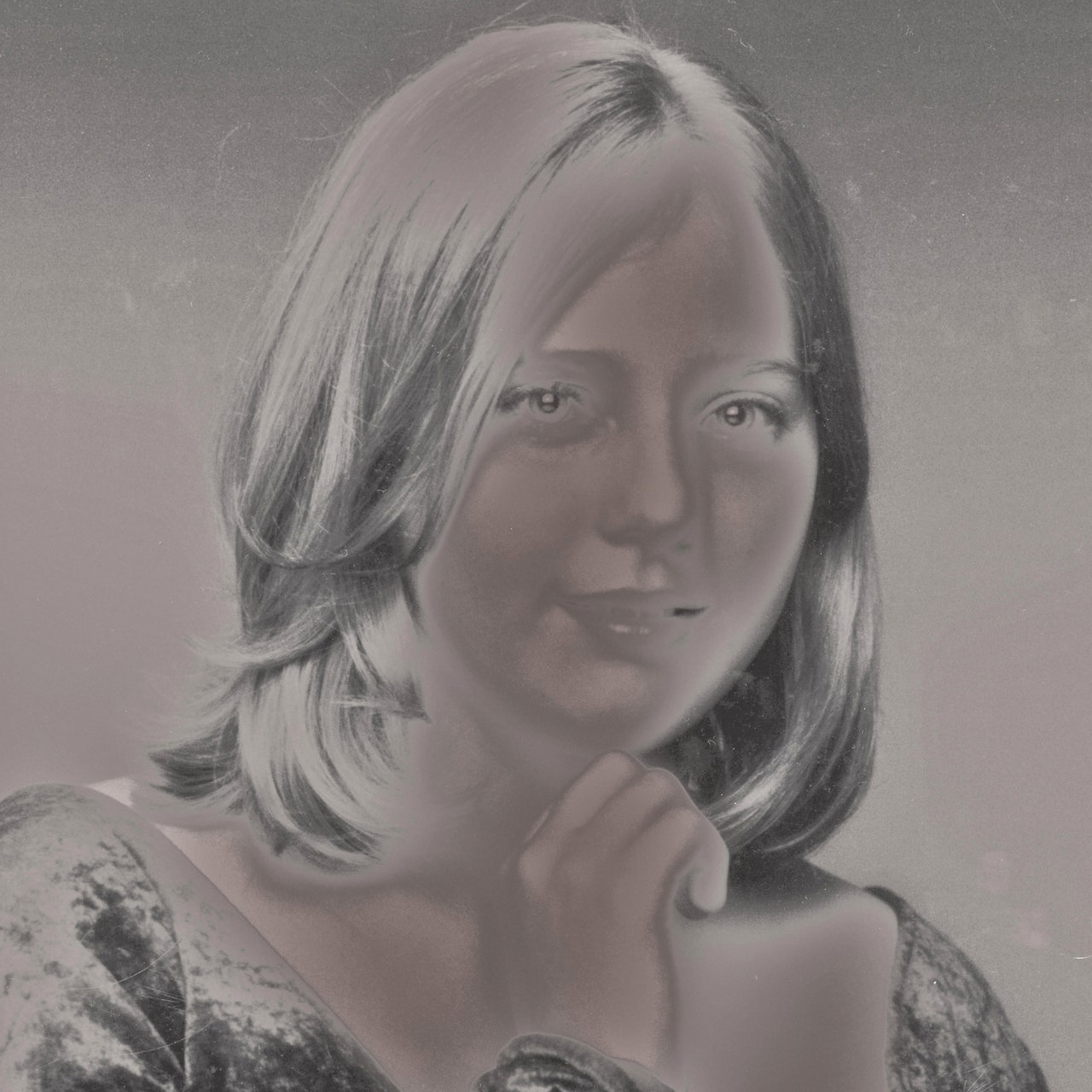

The American Girl is an expensive doll. She comes packaged with a history that follows a tidy narrative trajectory: She has and will overcome obstacles with grace, poise, and beauty. She will know no prolonged sadness, nor wonder as to her purpose. These are the promises on which she was raised. She knows the longer she stays in her box, the more she’s worth. But if she looks out at the world long enough, she’ll realize she’s only ever seen it through a warped plastic window. What’s an American girl to do?

Since her 2018 breakthrough, In a Poem Unlimited, the response of Meg Remy—the sole member of U.S. Girls—has been to embrace the hyperreal. Like a version of Neo who returns to the Matrix and becomes Patrick Bateman, she swallows up the plastic exploitation of the last six decades of American pop music and flaunts its excesses. If it’s typically impossible to tell when she’s satirizing and when she’s simply feeling the pleasure of singing and moving her body to a well-made song, that ambiguity is probably the point. On Scratch It, her most immediate and accessible album, she leaves the ’80s electro-funk of 2023’s Bless This Mess behind and remakes herself as a mid-’60s country crooner in a shimmering skirt. While it calls to mind Cat Power’s Memphis masterpiece The Greatest and the haunted beehive of Cindy Lee’s Diamond Jubilee, Scratch It buzzes with a chattering methamphetamine sleaziness, as much Vegas as it is Nashville. The TNN studio lights that frame this record are so hot, they make the music sweat.

As with most U.S. Girls albums, sweating is what this music most wants to do. Remy’s project is conceptually heavy, but what’s kept her uncanny avant-pop from being some tedious academic exercise—or, worse, a ribald pomo take on established styles—is that she always remembers to bring her body with her: “Under the street there is a beach,” she sings in 2023’s “Only Daedalus,” whose slinky quiet storm beat is a reminder that the situationists who turned that phrase into the slogan of the 1968 student protests saw pleasure as the end goal of liberation.

On Scratch It, she’s looser than ever before, letting the contradictions arise naturally rather than spelling them out. “James said you gotta dance till you feel better,” she sings in the opening “Like James Said,” quoting “Get Up Offa That Thing” while cheekily calling the man who demanded to be addressed as “Mr. Brown” by his first name. She flips the gospel standard “Just a Closer Walk With Thee” into a jam about the freedom of a good fuck. “You had boots on/I had bare feet/It was a natural conspiracy,” she sings, a David Berman opener delivered in a husky T-Boz register. “Firefly on the 4th of July” marches to a martial snap whose every beat is pillowed by a lead line from guitarist Dillon Watson that wanders and flits like a lazy bee. “Thank god I was looking good when I saw you,” Remy sings, a little sun drunk, delivering her lines with the relish of Jeannie C. Riley socking it to the Harper Valley PTA.