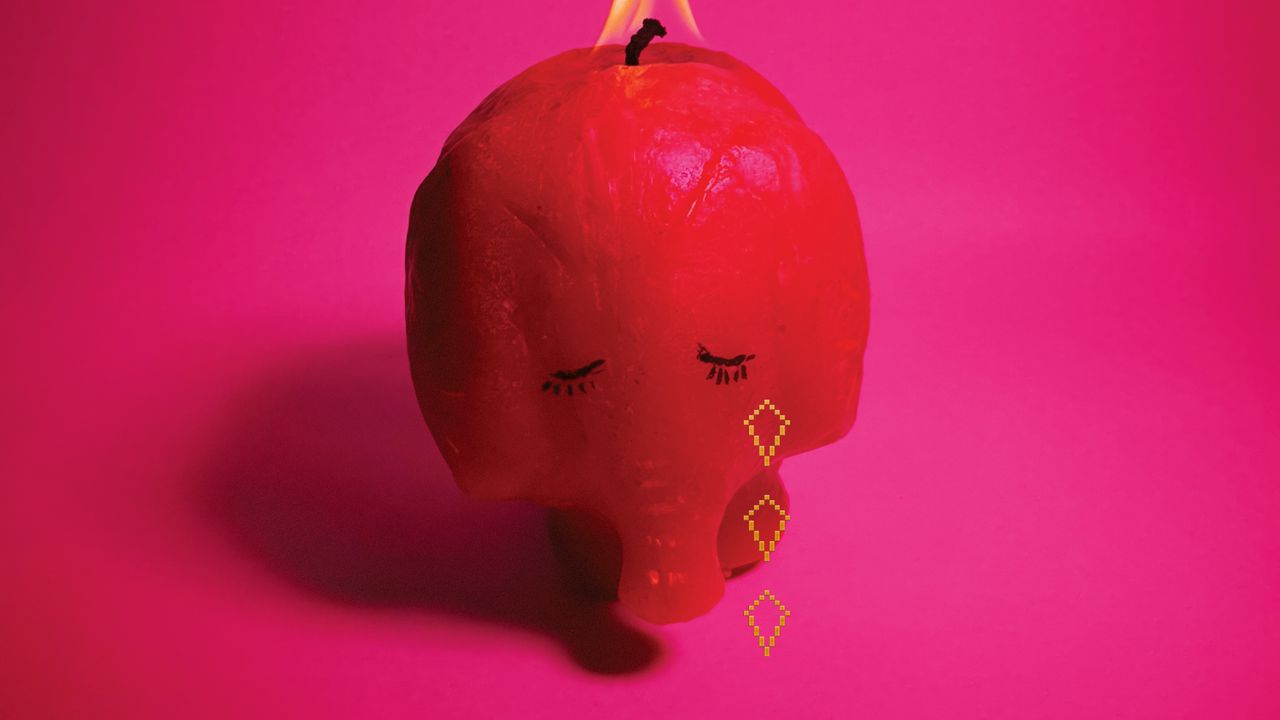

No verdict in the court of public opinion could be harsher than the one Arcade Fire have rendered upon themselves: They’ve created their own prison with Pink Elephant, a vow of penance that spends 42 minutes equivocating and demurring, against their every impulse to do the opposite. Win Butler is barely audible for the first half of lead single “Year of the Snake.” The album rollout has not inspired any credulous Hollywood Reporter profiles, interactive music videos, or fake websites. It barely lasted a month and has been accompanied by a near-total media blackout, save for a promotional tour of “intimate venues” and a frankly astonishing sixth appearance on Saturday Night Live. But the overall message has been clear: Arcade Fire would change their name if they hadn’t tried that already.

Of all the things Arcade Fire have learned from U2, nothing has taken hold like the goal of “reapplying” to be the best band in the world. But while Bono only said that once, Arcade Fire have spent the past 15 years since The Suburbs adjusting the cover letter and padding the résumé, desperate to figure out what the best band in the world is supposed to be. The irony and piety of 2017’s Everything Now and 2022’s WE cancelled each other out, attached to works of great effort and little conviction that made Arcade Fire seem equally unpersuasive as satirists or saviors. That was only accelerated by the accusations of sexual misconduct leveled against Win Butler in 2022. To whatever degree Arcade Fire were cancelled, the tours and SNL 50 appearances were not. You could argue that bigger monsters are thriving in relative peace, or that Butler is being punished less for his actions than for how they conflict with his reputation. So it is in a culture that’s more forgiving of creeps than hypocrites.

I might have avoided discussing this subject entirely if it weren’t the subtext and, sometimes, the text itself of Pink Elephant, casting a shadow far darker and longer than the still-imposing legacy of Funeral or The Suburbs. Arcade Fire spend Pink Elephant cowering in that shadow, offering ambiguous sloganeering, non-apology apologies, and arena rock that gets moved to the 1,500-cap venue due to sluggish ticket sales. The opening three-minute, lunar-roving drone of “Open Your Heart or Die Trying” promises a spiritual reboot, but also promises the same cinematic grandeur of other Arcade Fire albums. They repeat this trick twice more, which ends up having the opposite effect, exposing a threadbare motif that sticks Pink Elephant together like Scotch tape on a last-minute Christmas gift.