For 50 years, a copy of Ted Lucas’ sole, self-titled album felt like a secret treasure—a coveted charm you might pull out only when the closest friends dropped by, whispering “Have you heard this?” before putting the needle on a record that shouldn’t actually exist. In the early ’70s, Lucas was a frustrated Detroit guitar whiz in his early 30s. Two of his rock bands had already been dropped by Warner Bros., and his once-steady Motown session work with the likes of the Temptations and the Supremes was vanishing as the Motor City institution wheeled away for Los Angeles.

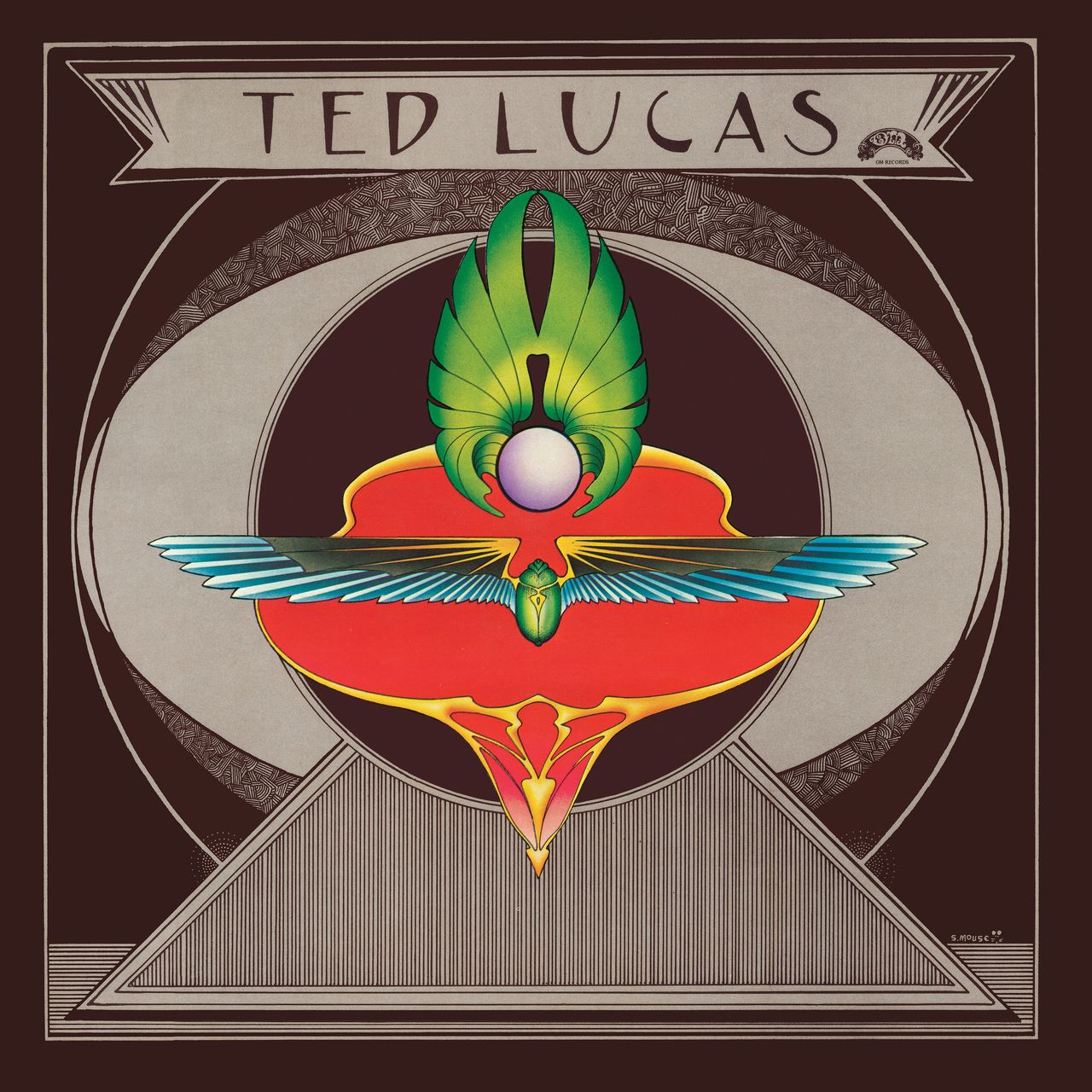

So Lucas multi-tracked six songs alone in his attic and dispatched the demos to Warner, only to be rejected again. He eventually added an instrumental second side, paid to press it twice on his half-real OM imprint, and distributed the thing himself in irritated fits and starts from home. The OM Record, as it came to be known, slowly emerged as a jewel accidentally tossed in the private-press folk dustbin. Even reissues—particularly a 2010 co-release by Willam Tyler’s retired Sebastian Speaks label—could command price tags above $100. Cited as an influence by Clairo and Devendra Banhart and covered by Mountain Man and Julianna Barwick, it is, after all, a magical little thing, as softly stunning as any other bit of idyllic psychedelia committed to tape amid the long afterglow of the lysergic ’60s. You had to keep your copy of The OM Album a secret; the songs are instantly addictive, and there just weren’t enough to go around.

After a half-dozen small editions during the last half-century, Lucas’ only LP is, at last, permanently available thanks to Third Man Records. Motivated in part by their mutual Detroit origins, co-owner Ben Blackwell is leading the first true archival excavation of Lucas, moving beyond these nine mostly perfect songs to explore the full scope of his chameleonic music—and his self-sabotage within the music industry. The project starts, as it should, with a generously expanded reissue of The OM Album. Four digital-only bonus tracks instantly prove this wasn’t some fluke, while the concise but expansive liner notes by Detroit music historian Mike Dutkewych finally explore the backstory of someone so mysterious and magnetic that he has been rumored—at various points, and with no real corroboration—to be the inspiration for “Mr. Tambourine Man.” This is the full treatment these songs have so long deserved.