There is a bowel-deep grumble that rolls over the frames of David Lynch’s films. The drone is an unsettling but crucial companion to his scenes, one that roils beneath a frightening encounter in Lost Highway and roars atop Henry’s paternal sin in Eraserhead. At times, it can be difficult to determine whether these drones are seeping from an external evil lurking in Lynchland or from within the characters themselves. Diegetic or non-diegetic? Real or imagined? If you asked Lynch to settle this query, he’d likely just smile.

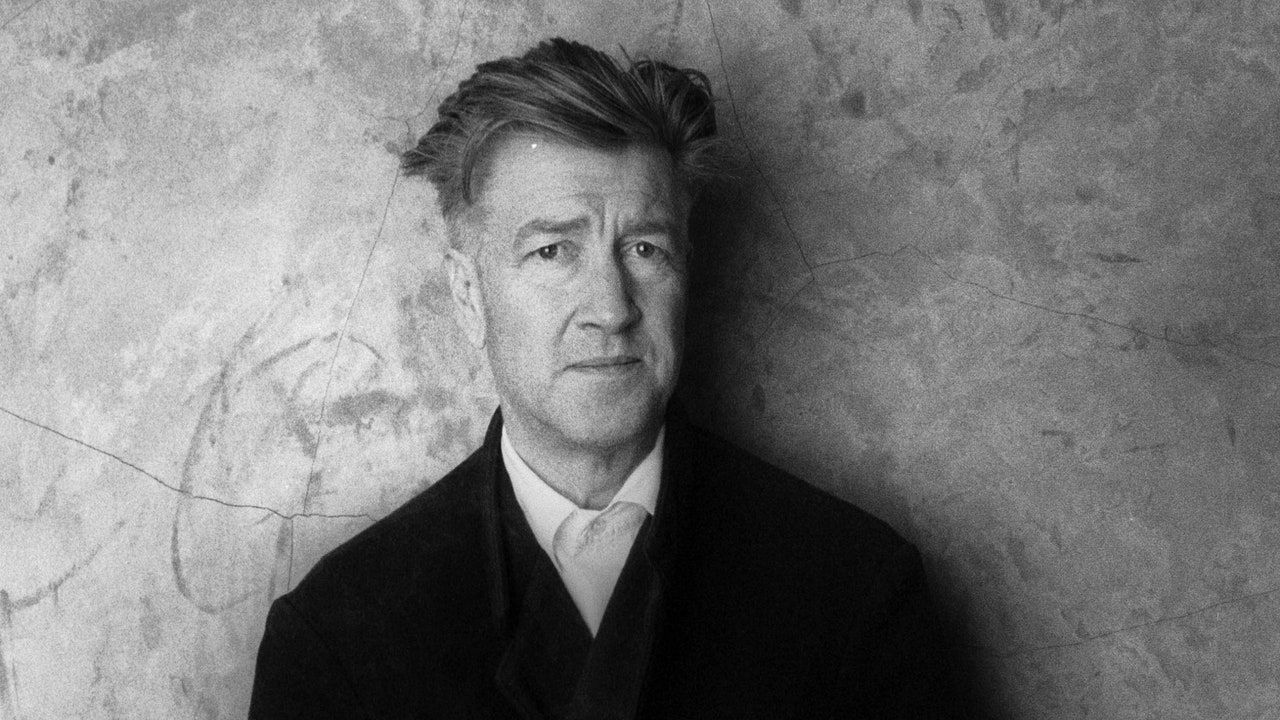

David Lynch, the peerless filmmaker who died this week at the age of 78, was in love with the mysteries of life, and though he examined them as a painter, musician, and armchair philosopher, we will always remember the mysteries he presented—in vivid color and occasionally grotesque detail—on screen. His surreal, operatic films and television shows examined romance, consciousness, evil, and the enduring rot beneath suburban sheen and Hollywood glamor. Throughout all of his work, perhaps most memorably in the warped noir of his television series Twin Peaks, Lynch steered composers to create music as inexplicably haunting as his moving pictures.

“Cinema is sound and picture both—50/50 really,” Lynch told The Guardian this past summer. “I don’t know why everyone doesn’t think this way.” Music and sonic ambiance were inextricable from Lynch’s filmmaking, and he conjured them from the same well of sense memories as his indelible imagery. Lynch directed musicians like actors, giving longtime collaborators like Angelo Badalamenti and Julee Cruise emotional prompts to guide their performances, or requesting sounds that had a tactile or visual analog.

As Cruise told it in a 2016 interview with Pitchfork, Lynch, while co-producing her single “Rockin’ Back Inside My Heart” with Badalamenti, kept shouting “big chunks of plastic!” at the saxophone player. Nine Inch Nails mastermind Trent Reznor, who worked on the soundtrack for Lost Highway, recalled in the same interview a piece of similarly abstract direction he received from Lynch: “He scribbled something in a star-like pattern with an ink pen and said, ‘I would really like it to sound like that.’” As for that haunting drone, Lynch recently traced its source to a happy memory: Watching B-52 bombers fly in formation in the Pacific Northwest, where he lived for a few years as a child.

Lynch’s ability to hear shapes in sound, to facilitate their sculpture by his collaborators, was just one facet of his multi-sensory approach to art. Another expression emerged from everyday objects, which inspired Lynch to deform the mundane into a hellish din. The pinnacle of such lovingly crafted unease is Lynch’s 1977 feature debut, Eraserhead, which buries its first bits of dialogue 11 minutes into a 90-minute film. The opening sequence is a protracted panic attack fueled by sonic foes: the roars and whirrs of overdriven machinery; clattering silverware; a radiator squeal that punctures the cochlea like a darning needle.

Lynch developed Eraserhead’s sound design alongside late collaborator Alan R. Splet, who also worked with Lynch on The Elephant Man, Dune, and Blue Velvet, before Splet’s death in 1994. The two men spent months on the soundtrack alone. Lynch sought to capture the industrial hellscape of 1970s Philadelphia as he experienced the city he called home for nearly a decade. “It was one of the sickest, most fearful, corrupt, frightening cities I’ve ever set foot in,” Lynch said in a 1986 television interview. “I feel the atmosphere of a place, the mood of a place, and I just felt I was living inside an ocean of fear.”

Blue Velvet, though massively scaled down from the sonic assault of Eraserhead, also magnifies and warps ordinary audio into a sinister roar. The pressurized rattle of a hose spigot warns of imminent disaster. Beetles claw through a manicured lawn to evoke disembowelment. That these noises, terrifying and oppressive, blare from such familiar sources, is at the heart of what’s so frequently referred to as Lynchian: It’s coming from within your house—or maybe within you.

“Lynchian” is a word that gets thrown around a lot, especially in music criticism. This site alone has used it at least 60 times, as my editor recently pointed out. (I’m guilty myself.) It is invoked when ethereal, synth-driven melodies remind writers of Badalamenti’s soaring Twin Peaks score, or if singers grasp at the gossamer dream pop Cruise recorded for the show. Lynch might as well have put the “dream” in “dream pop”; his films created an all-new cinematic language for the fluidity of the dream state. The dead walk again, words stall and hiccup like gnawed tape reels, a single soul can slink between bodies with zero narrative disruption.

Some reserve the word “Lynchian” to simply describe a guitar or saxophone riff reminiscent of the skewed lounge music in so many of Lynch’s films. Even the lounge noir aesthetic of those scenes—blood-red drapes, geometric flooring, tragic women done up like silver screen idols—has seeped into musicians’ visual lexicon. Johnny Jewel, whose band Chromatics was one of several groups to play the Roadhouse in Twin Peaks: The Return, is especially dedicated to the vamped-up vintage look Lynch mastered, though his interpretation is far less painterly.

At the core of Lynchian art is unnerving contrast: a picturesque lumber town home to a heinous murder; a gleaming Hollywood production corrupted by insidious mobsters; a Reagan-era golden boy who slips all too quickly into sexual violence. The latter case refers to Kyle MacLachlan’s Blue Velvet character Jeffrey Beaumont, who uncovers a deranged criminal conspiracy lurking in the shadows of his picture postcard hometown. “I’m seeing something that was always hidden,” Jeffrey tells his companion Sandy (Laura Dern) as he rifles deeper into a cesspool of kidnapping, rape, drug trafficking, and murder. Lynch’s scope of humanity, specifically of middle-class American humanity, was both compassionate and dismal. As the malignant Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper) says to Jeffrey in a pivotal scene: “You’re like me.”

Songwriters like Lana Del Rey and Ethel Cain, both of whom have been called “Lynchian” artists countless times, utilize the central contrast in so much of the filmmaker’s work. Del Rey, a longtime Lynch fan, often pits sweeping, cinematic flourishes against gritty and imperfect reflections of womanhood. Cain’s 2022 debut, Preacher’s Daughter, meanwhile, mined the grim underbelly of the American South and transposed it all into airy pop anthems. But Cain’s new album, Perverts, smacks of an earlier Lynch; its dark ambient groans and machine-like dissonance underscores the flesh-bound sensations of sexual shame and bodily discomfort. Bill Callahan’s early work, primarily under his Smog moniker, felt almost diseased with Lynchian imagery: flatly-sung, plain-lit displays of violence, perversion, and rural delights.

There is something Lynchian, too, in the tragic characters of Del Rey and Cain’s respective work. Lynch frequently depicted doomed women on stage, singing with the devastation of Madame Butterfly. In Blue Velvet, Dorothy Valence’s (Isabella Rossellini) rendition of the title ballad is a conduit for her internal life. Rossellini’s wavering, pitchy delivery is no mistake, but an embodiment of Dorothy’s suffering—all doused in the cheap glamor of a small town nightclub.

“If you saw a film and the beginning of the film was peaceful, the middle was peaceful, and the end was peaceful—what kind of story is this?” Lynch said in one of his last interviews. “You need contrast and conflict in order to tell a story. Stories need to have dark and light, turmoil, all those things.” Lynch spent his years making films that seeded purity with malignancy, machismo with vulnerability, teenage love with mythic importance. He knew that these contradictions, so integral to his own art, are at the core of our humanity.