The Innocence Mission have been around so long that they know what it’s like to both capture and practically fall out of the cultural consciousness. When the original four members met back in the early 1980s, during their Catholic high school’s production of Godspell, they couldn’t deny their congruities: warm, easygoing, soft-spoken students with a knack for folk-rock and dream pop. Fast forward a few years and the Innocence Mission was born: primary singer-songwriter Karen Peris and guitarist Don Peris got married, their debut album came out on A&M in 1989, and comparisons to Kate Bush and the Sundays earned them a cult following. Depending on how old you are, you might know the Innocence Mission from their interviews on MTV’s 120 Minutes, appearances on Late Night With David Letterman and the Empire Records soundtrack, or Sufjan Stevens’ breathtaking rooftop cover of “The Lakes of Canada.” Now long out of the spotlight but with a sound that’s largely unchanged, the husband-and-wife duo and original bassist Mike Bitts are approaching the end of middle age on Midwinter Swimmers, their 13th album, with even more unbarred earnestness, a sharp contrast to the jaded stances permeating modern life.

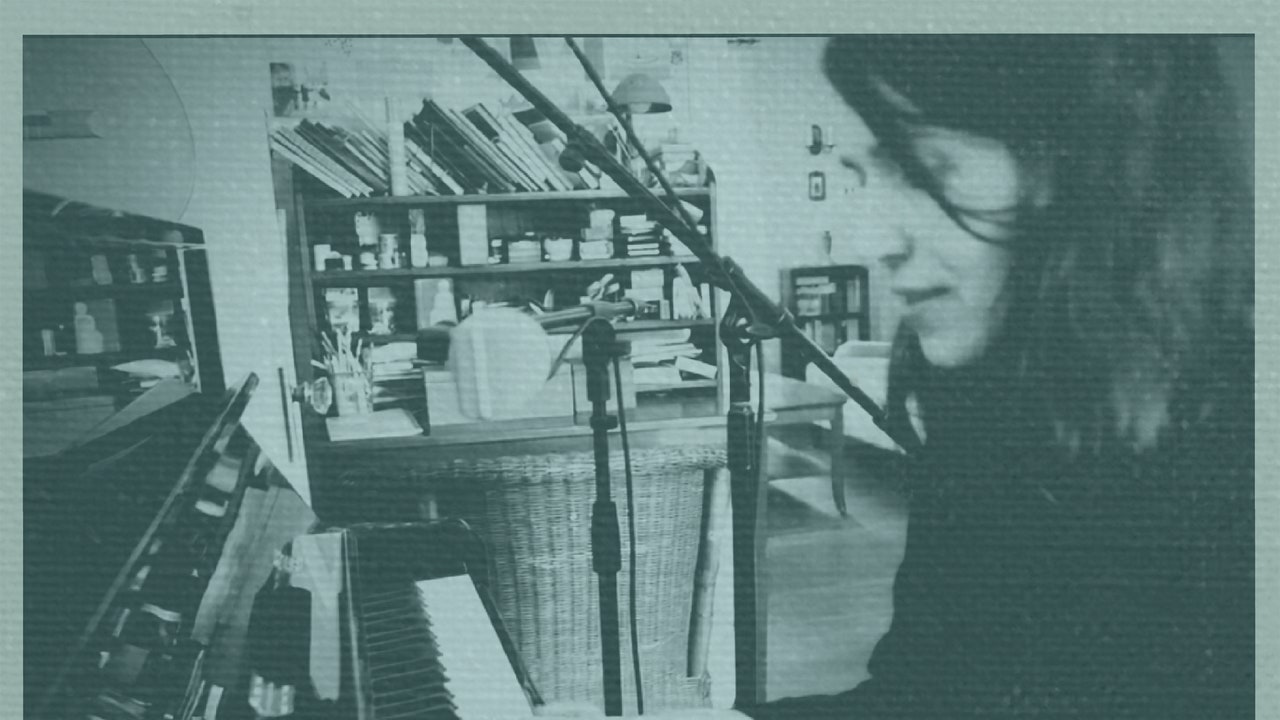

Now nearly 40 years into her recording career, Karen Peris’ voice remains as delicate and angelic as when she was a teenager—and still unmistakably her own. Close your eyes and it’s the voice Matilda imagined Miss Honey having: delicate, sprightly, encouraging; her chirp fit for innocent conversations between book stacks (an Innocence Mission dreamscape lucky Borders shoppers once stumbled across). That weightlessness turns the album’s title track into a curious and soothing tale of longing, and “Your Saturday Picture” into an evocative tale of yearning with childlike insouciance. Occasionally she crunches a word in her mouth like Björk, wide and mawkish, like each “sing on” uttered in “Sisters and Brothers.” Even when sadness seeps into her heart seconds later (“I lost something I used to be before/I don’t know why I’m crying”), Peris finds equanimity in the way tree branches and birds carry on in troubled weather. While her husband plucks and strums various guitars to add texture, Peris’ sweet voice summons cottagecore imagery naturally: leafy rhubarb, Appaloosa horses, leaves falling onto her head like a crown. It’s no wonder she was once invited to sing on Joni Mitchell’s Night Ride Home.

With age, Peris’ stories have grown more personal and straightforward, though not without their usual charm. Midwinter Swimmers is an album born from observations on her daily walks and pangs of longing during time apart from her husband. She cultivates a grand vision of romance in a song about their alternate dream life on the coast of Maine, living alongside sunlit moss and a picturesque striped lighthouse. But it’s the little asides dotting each track that showcase her affection best: “Saving up all these things to tell you,” ”Wait for me/I miss all the buses lately,” “I would race all the blocks of town to you.” Karen and Don Peris structure these songs to burst with love in the glow of ’60s folk pop, and the rush of those highs—the back half of “This Thread Is a Green Street” cascades with lavish harmonies and a surprise rhythm-section reveal—draws a straight line through the influences from their childhoods: the Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel, James Taylor. “In five o’ clock raindrops/You stop to take a picture/Of you and me,” she sings in “Cloud to Cloud.” “We’re carrying guitars, groceries, and flowers/Everything is light.” Illustrating the tender moment in full color, Don leans heavier into his drumkit and electric guitar while Karen answers with melodica, a playful back-and-forth of musical PDA.