James Earl “Jimmy” Carter Jr., the 39th president of the United States, has died, the Carter Center announced. He had been in hospice care since February 2023, and his wife, Rosalynn Carter, died in November 2023. The former president was 100 years old.

“My father was a hero, not only to me but to everyone who believes in peace, human rights, and unselfish love,” one of Carter’s sons, James Earl “Chip” Carter III, said in a statement. “My brothers, sister, and I shared him with the rest of the world through these common beliefs. The world is our family because of the way he brought people together, and we thank you for honoring his memory by continuing to live these shared beliefs.”

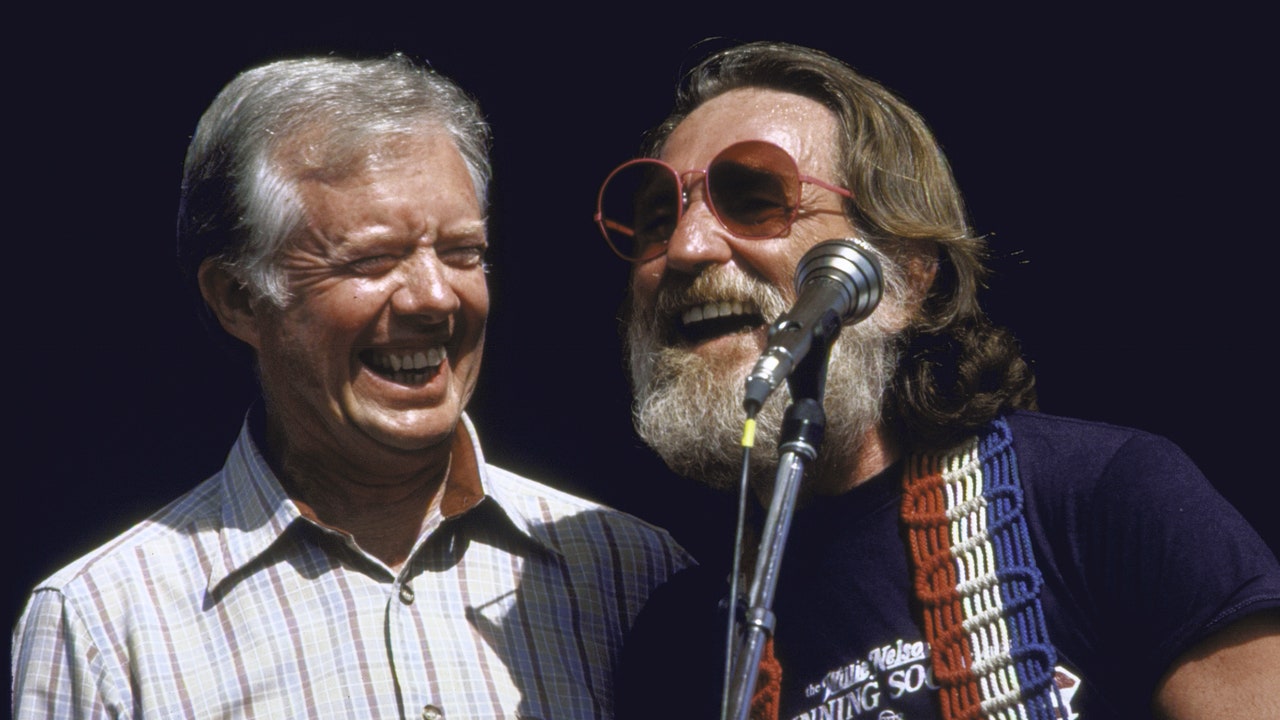

Hailing from a peanut-farming family in rural Georgia and a distant cousin of the Carter Family, Jimmy Carter had a unique affinity for music that he carried all the way to the White House, emphasizing music as an important cultural presence and point of connection for all people. He was especially close with Willie Nelson, Bob Dylan, and the Allman Brothers. Carter’s genuine passion for music provided him an avenue of association with his colleagues and constituents alike, which became an important soft-power tool in the wake of Richard Nixon’s ignominious administration. His affection was captured in the 2020 documentary Jimmy Carter: Rock & Roll President.

Carter began his political career in 1962, winning a seat in the Georgia State Senate. His love for music was formative from a young age, beginning with his upbringing around gospel songs in church. He called gospel “rural music,” saying, “it has both Black and white derivations. It’s not a racial music… it’s a music of pain, of longing, of searching, of hope, and of faith.” Carter’s rise in politics coincided with the civil rights movement, and, as a white man in Georgia politics, he spoke with uncommon clarity and resolve against racial segregation.

By the time Carter was at the forefront of the New South movement in the early 1970s, his home state was known as a hotbed of powerful musical output, including James Brown, Ray Charles, and Otis Redding. The Allman Brothers, who made a home of Macon, Georgia, were recognized as being one of the first racially integrated rock bands by 1970, and the group’s blend of rock with rhythm and blues appealed to Carter easily. His love for all types of music aligned with his fervently held belief that humans have a universal right to dignity and free expression. When Carter took office as the governor of Georgia in early 1971, he declared in his inaugural speech, “The time of racial discrimination is over.”

During his term as Georgia’s governor, Carter found further wisdom and relief in the music of Bob Dylan, which he learned about through his sons. He invited Dylan and his bandmates to visit the governor’s mansion in Atlanta, where Carter said Dylan asked him about his religious beliefs. Dylan said the encounter was the first time he realized that his music had crossed over to the “establishment,” rattling him slightly. “[Carter] put my mind at ease by not talking down to me, and showing me that he had a sincere appreciation of the songs I had written,” Dylan attested in Rock & Roll President. “He’s a kindred spirit to me of a rare kind.”

Phil Walden, Otis Redding’s former manager and president of the Macon-based Capricorn Records, aided in recruiting the Allman Brothers to put on fundraising shows for Carter’s 1976 presidential run. The Allman Brothers stumped for Carter as they toured the United States, helping him get a stronger foothold on the national political stage and giving his campaign a much needed financial boost. Jimmy Buffett, John Denver, Toots and the Maytals, the Marshall Tucker Band, and Charlie Daniels all supported Carter in his successful presidential bid.

Both John Lennon and John Wayne attended Carter’s inaugural celebration in early 1977, speaking to Carter’s ability to connect across political lines. Aretha Franklin sang “God Bless America” at Carter’s request, and Paul Simon dedicated “American Tune” to the new president, saying, “Perhaps a time of righteousness and dignity may now be upon us.”

Music remained an important part of Carter’s White House tenure, with his administration hosting concerts that celebrated American music, highlighting gospel, country, blues, and jazz. As Carter welcomed visitors like Dolly Parton, Charles Mingus, and Crosby, Stills, and Nash, he remained close with the music-makers he’d befriended in his gubernatorial days. One visit from Willie Nelson has endured in cheeky infamy: The Texas singer-songwriter wrote in his 1988 autobiography that he’d smoked marijuana on the roof of the White House.

In 1978, the White House hosted a celebration of the 25th anniversary of the Newport Jazz Festival, bringing Dizzy Gillespie, Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, Max Roach, and more to the South Lawn. Carter asked Gillespie to play his song “Salt Peanuts,” and Gillespie obliged, on the condition that that the president sing the lyrics along with him. “I’ve got one question: Would you like to go on the road with us?” Gillespie asked Carter at the end of the performance. “I might have to after tonight,” Carter joked in response.

Despite his folksy popularity, Carter’s term was disrupted with issues like oil shortages, stagflation, and the Irani hostage crisis. He lost re-election to Ronald Reagan in 1980. Although Carter served only one term as president, in the four decades after he left office, he maintained a commitment to public service and diplomacy, broadly emphasizing human rights and progressive values. Carter’s Habitat for Humanity nonprofit recruited Garth Brooks, Trisha Yearwood, Kelly Rowland, and more to help build new homes. He advocated for Palestinian independence with his 2007 book Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid, which minted a new friendship with Peter Gabriel, who cited Carter as a major inspiration for his own interest in progressive activism.