Robert Palmer spent his long career perched between rock stardom and cult fame. He became one of the key artists of MTV’s golden age thanks to “Addicted to Love,” a crunching rocker married to a video that mitigated exploitation with irony. The sight of Palmer performing in front of an army of anonymous supermodels became one of the iconic rock images of the 1980s, pushing “Addicted to Love” to the top of the Billboard charts in 1986, 12 years after he launched his solo career with Sneakin’ Sally Through the Alley.

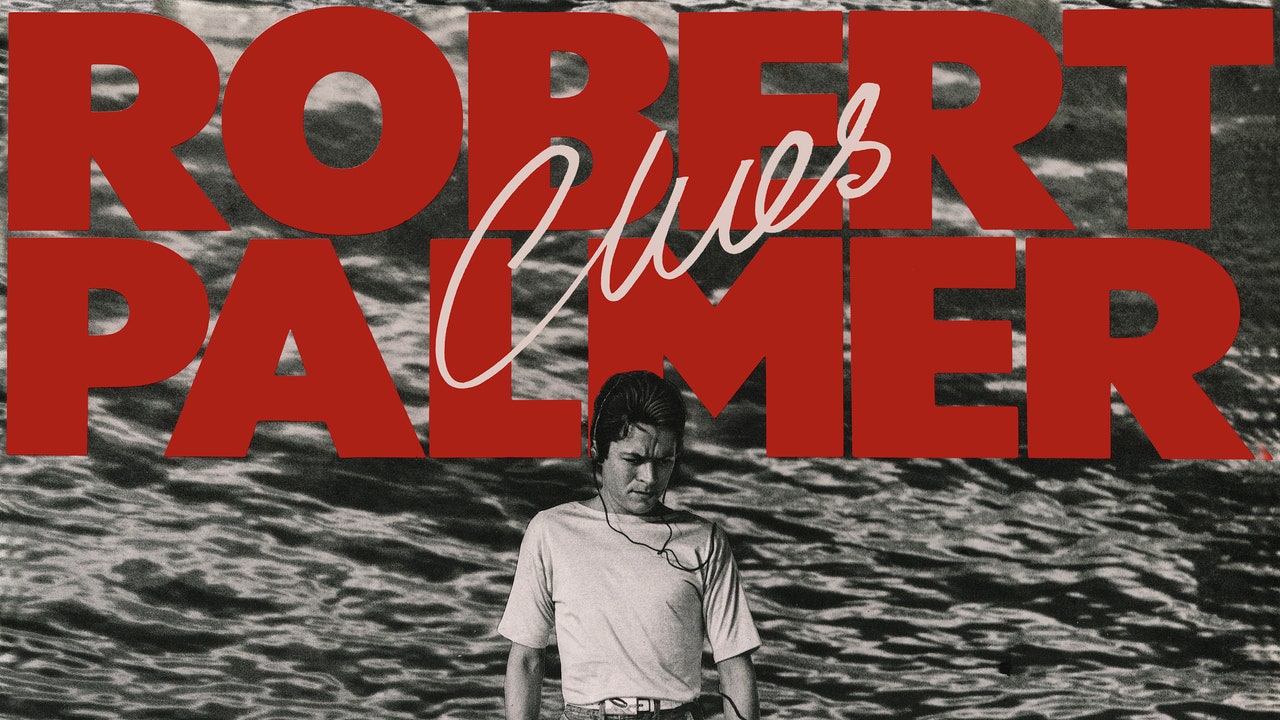

Clues, Palmer’s sixth record, appeared in 1980, halfway between that 1974 debut and Riptide, the parent album to “Addicted to Love.” Fittingly, Clues sounds as if it’s caught between two worlds, attempting to shed the skin of the album-oriented 1970s as it evolves into the electro futurism of the 1980s—a metamorphosis vividly captured on the album’s two singles, “Looking for Clues” and “Johnny and Mary.” Palmer wasn’t the only rocker dabbling in new-wave fashion in 1980. The underground started to bubble up into the mainstream that year, with Alice Cooper’s Flush the Fashion, Linda Ronstadt’s Mad Love, and Paul McCartney’s McCartney II all incorporating the sequenced synths of new wave.

When he released Clues in September 1980, Palmer was nowhere close to being in the same league as those rock stars. He was a journeyman, one whose first big break arrived via Vinegar Joe, a hippy hangover he co-fronted alongside Elkie Brooks. Too slick for the underground, too shaggy for the mainstream, Vinegar Joe released three records in the early 1970s that demonstrated Palmer’s gritty rasp and appealing sense of control, not to mention his superior sense of taste, at least compared with the rest of the outfit. These characteristics caught the eye of Chris Blackwell, the head of Island Records, who signed Palmer to a solo contract that allowed the British singer to surround himself with expert American musicians. On Sneakin’ Sally Through the Alley, he counted the Meters and Little Feat’s Lowell George among his supporting musicians.

Palmer kept pace with ease; his unflappable delivery suggested he was holding some energy in reserve. He began to thread reggae into funk on Pressure Drop, a record where he shared the album cover with a naked woman, the first in a trilogy depicting Palmer as a mischievous playboy: He’s winning a game of strip poker on Some People Can Do What They Like, grinning over a pair of discarded bikinis on Double Fun. A satiny veneer enveloped his records, yet he kept his arm’s distance from pop; he remained a resolutely album-oriented artist, barely scraping the Billboard charts as he doggedly toured America.