“Do you remember?” are Fred Thomas’ first words on Window in the Rhythm—and the subtext for every lyric that follows. Can you recall every sound, sight, and smell from a 2002 DIY show, but not where you left your keys five minutes ago? Ever search for your wretched student rental on Google Street View? If so, you’ve got a potential Fred Thomas song in you. Though Thomas is usually juggling three different projects at any given time, he’s an Ann Arbor Proust on his solo records, swapping a madeleine for the shittiest slice of Backroom pizza. But his reveries are no longer content to accept nostalgia alone as an endgame. On Window in the Rhythm, Thomas dares to ask why you remember.

The album is an unexpected coda to the indie-lifer trilogy Thomas ostensibly completed with 2018’s Aftering. Those albums were cobbled together like mixtapes, collaging twee-pop, folk-punk, Elephant 6 fan-fic, and abstract electronica, to better represent the full scope of his interests. (One such mixtape turns up in the opening “Embankment,” where he sings, “I made you a tape with the same Squarepusher song on it four times, but not in a row/To mimic the way so much was haphazard/The abundance of magic in a fragmented flow.”) This time around, Thomas name-drops Joanna Newsom’s Ys as a primary influence. His story checks out: There’s harp in the credits (by Mary Lattimore and Shelley Burgon) and the average song length is eight and a half minutes. But the basics of Thomas’ sturdy songcraft haven’t changed; discursive, sung-talked verses just take the scenic route before jolting upright into tightly wound, Motown-inspired harmonies.

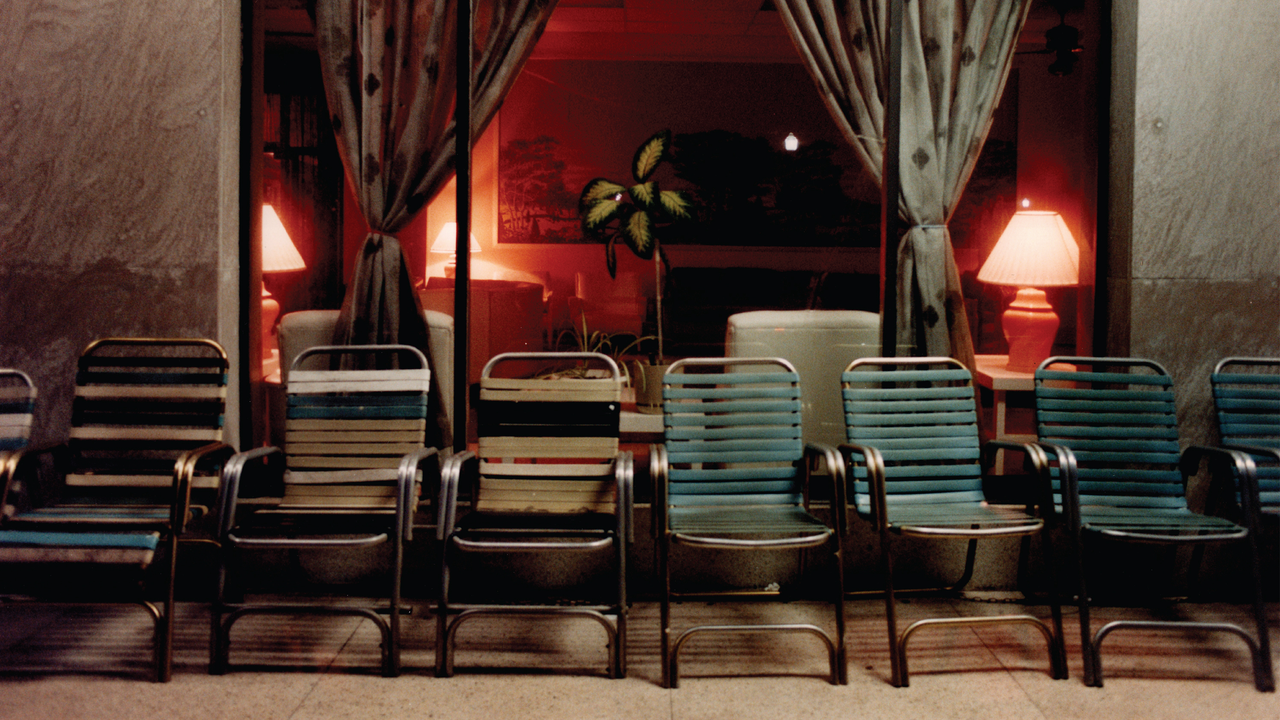

Thomas’ memory transcends “photographic” or even “cinematic.” His most evocative writing yet creates a sensual feast of all drabs—“the dull, bathwater-colored glow of every Adderall halo”; “dingy gray water in a vase”; “an ugly, unwashed tie-dye tee”; “mattress on the basement floor/Black sheets hung in place of doors.” In any of those images, the taste of stale Pabst comes back so strongly, I felt the urge to pop three sticks of peppermint gum.

Like any search for lost time, it’s all inherently indulgent, and though even casual lurkers might catch the references to his early emo outfit Lovesick, the lyrics sheet probably should’ve come with annotations. Yet not a single second feels wasted, not when the whole point is to restage the formless stretches of a mid-20s that only take shape in retrospect: perpetual Novembers and rusting springtime bicycles, days arranged around perfunctory parties and dead-end jobs. The supersized closer “Wasn’t” is half feedback drone, but even that decision supports Thomas’ mixtape mindset by pushing Window in the Rhythm to exactly one hour. “Coughed Up a Cufflink” feels downright efficient, condensing the silence of an all-day trek through the Midwest into 10 mesmerizingly tense minutes. Midway through, a brief glimpse from the past expands into a full-on melodrama: