Have the Cure ever been truly young? Even as teenagers in England’s punk era, there was something suspiciously adult about this darkly elegant band from Crawley, who favored introspective Saturday nights at home, listening to dripping taps while keeping their tear ducts firmly buttoned up.

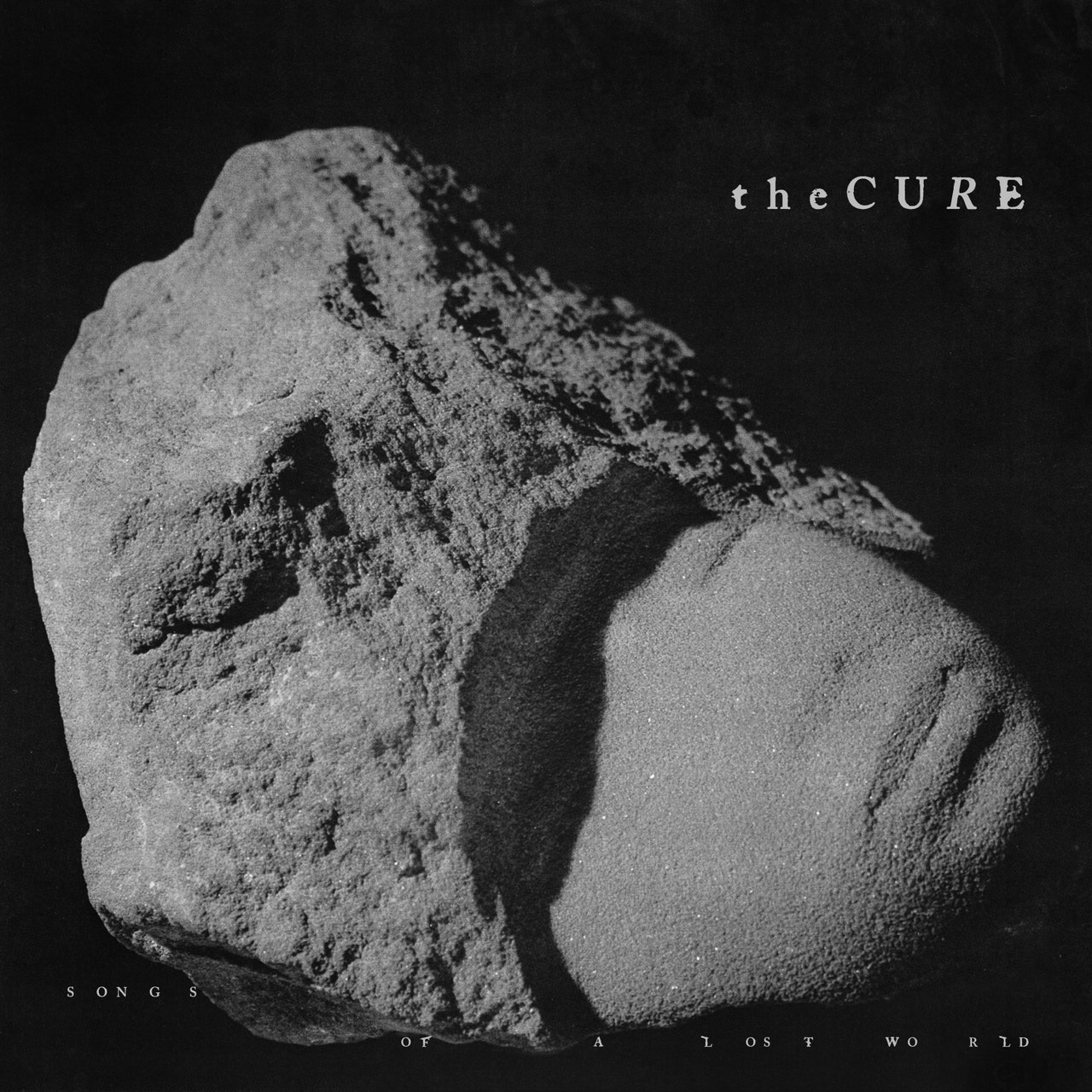

Perhaps this is why maturity suits the band so well. It has been 16 years (and two Kate Bush albums) since the last Cure LP and three decades since their last hit song. And yet Robert Smith & co. keep plodding on magnificently in a world of three-hour concerts, forever following their muse, free of the wearying obligations that face the next bright young things. Now, at last, they return with Songs of a Lost World, an album clearly uninterested in making up time after its prolonged gestation, and content to move at its own unhurried pace.

Of course, the Cure have had moments of giddy and joy over their four decades of life. But Songs of a Lost World has no gorgeously silly love songs like “The Lovecats”; no blood-pumping pop rushes like “Just Like Heaven”; no barrelling psychedelic jaunts like “The Caterpillar,” and no attempt to engage with the two billion-odd people born since the band last released an album. Nothing here—bar, perhaps, the riffy strut of “Drone:Nodrone,” a song of steely, gothic funk—raises the tempo beyond a stroll or threatens to push the temperature beyond a cold sweat. Instead, the Cure sound deliciously slow, elegantly weary, and definitively grown up on their 14th studio album.

Songs of a Lost World may be going nowhere fast, but that doesn’t mean it’s going nowhere. “Alone,” the opening song, is an object lesson in the way rock music can age gracefully. Reeves Gabrels’ gloriously jagged guitar pulls at the hair of Jason Cooper’s stadium drum thump while ethereal keyboard lines keep gentle watch. It’s an epic, thunderclouds-over-the-mountaintop production that shuns the callous energy of youth in favor of sober reflection, wrapped up in a beautifully pensive chord progression. When Robert Smith finally steps to the mic, three minutes in, and proclaims, “This is the end/Of every song that we sing,” it feels apocalyptically right, like the odd comfort of having your worst fear realized.