Rave culture got a late start in Japan, gaining traction in the early ’90s as club music was changing overseas. Having reached a point of critical mass, dance genres were seeking to reinvent themselves. Some artists were dialing back the momentum and turning their focus to ravers seeking an escape from the energy of the floor. British duo the KLF pivoted from the booming stadium house they’d helped pioneer and dreamed up the woollier ambient house. Soon after, Warp released the first of their Artificial Intelligence series, planting the seeds of what would eventually become known as IDM. These records resonated with Japanese producers as they prepared to build their own scene from the ground up.

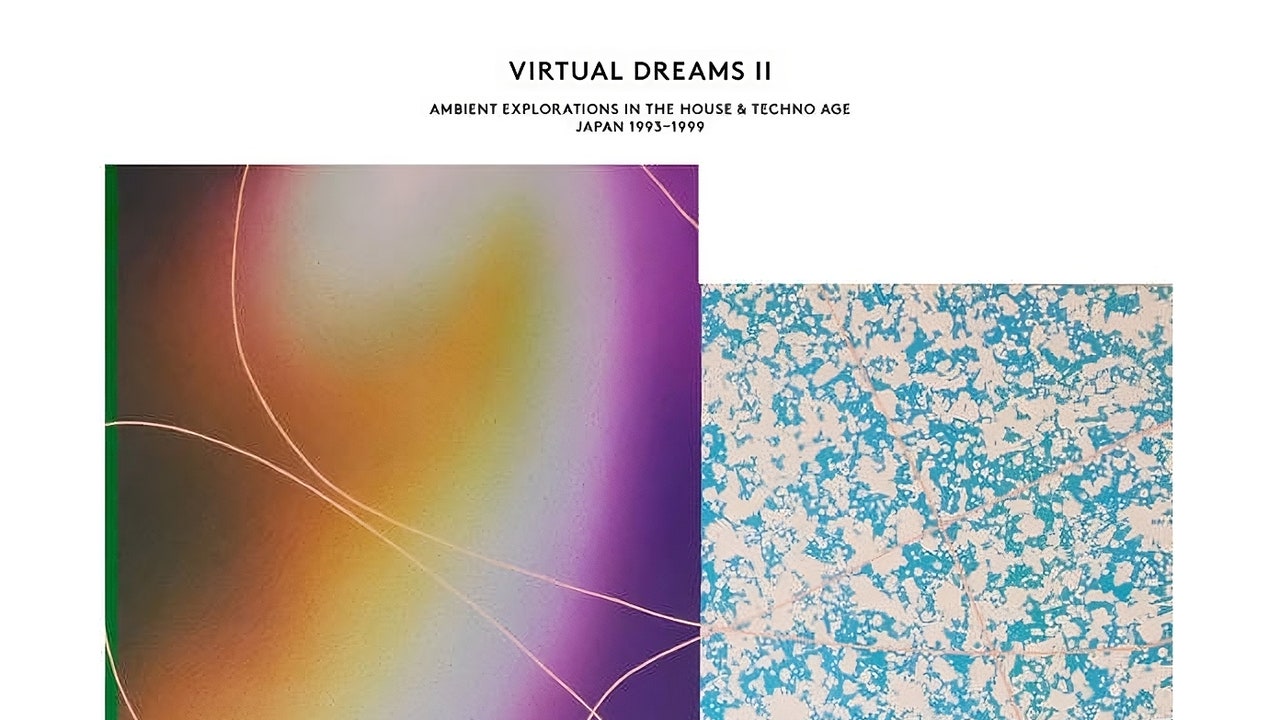

Virtual Dreams II: Ambient Explorations in the House & Techno Age, Japan 1993-1999, assembled by record store owner Eiji Taniguchi and the late Music From Memory cofounder Jamie Tiller, tells the story of how Japanese DJs and dancers found their own way to the dancefloor. These early forays into techno were more sedate affairs than their Western counterparts. Ambient soundscaping provided an interesting detour in European and American dance music, but it was on many Japanese artists’ minds from the beginning. Katsuya Hironaka’s “Pause,” for example, incorporates a thumping four-on-the-floor rhythm, but only briefly, instead drawing your ear to glimmering tones underneath and low roar of a field recording as it falls away. It’s the start of something new, but also an extension of Japan’s ambient boom from the prior decade.

One artist who was instrumental in these early years is Ken Ishii, who set the tone with his slower, more cerebral approach. In 1992, while still a student in college, he mailed a demo cassette to Belgian techno titans R&S—and to his surprise, the label signed him. His records started getting play around the world, and he was thrust into the position of ambassador for his country’s dance scene. Ishii’s decision to release his sophomore album, Reference to Difference, as the flagship release on the Japanese imprint Sublime was significant; it gave the label a boost, providing them the funds and name recognition to scout more talent. One of those early signees was Akio and Okihide, who achieved a bit of international success themselves on UK label Rising High. On “Phoenix at Desert” they eschew propulsive rhythms almost entirely, taking Ishii’s toolkit of warbling tones and stretching them into infinity. Already, a common musical language was developing.