You ever see a group of strangers in a bar so overcome with emotion—maybe the Bills won or they got the dream job; maybe the Bills lost or they just got laid off—that they start to spontaneously sing together, their off-key howls somehow finding a kind of universal tune? Everything is a shout chorus. They sing because they’ve been crushed by a first love but they’re ready to give up all this—the beers, the boys, the game—to experience the rush of young romance again. Sometimes they’re singing “Mr. Brightside” by the Killers; sometimes it’s “American Girl” by Tom Petty. If they’re really drunk or it’s St. Patrick’s Day (or both), they’re singing “The Boys Are Back in Town” by Thin Lizzy. Man, that must feel so good.

Japandroids are a band premised on these nights: dreaming about them, living them to the fullest, reminiscing about them fondly afterwards. In their full-throated commitment to debauchery and brotherhood, they counterintuitively avoided the pitfalls of toxic masculinity, celebrating the ecstatic possibilities of hanging out instead of lamenting its contemporary limitations. Despite what Tony Soprano said, Japandroids made “remember when” sound like the highest form of conversation, a lost art of keeping the fire burning. But nostalgia as fuel is always a risky proposition: Once it’s burned dry, it’s hard to keep the lights on. Fate & Alcohol, announced as Japandroids’ final album, strives to rekindle the same spirit that made their first three records sound like the best version of a night of drunken revelry. But with too few innovations and too many well-worn tropes, it lands like those two lonely guys at the bar trying to keep the party going after closing time.

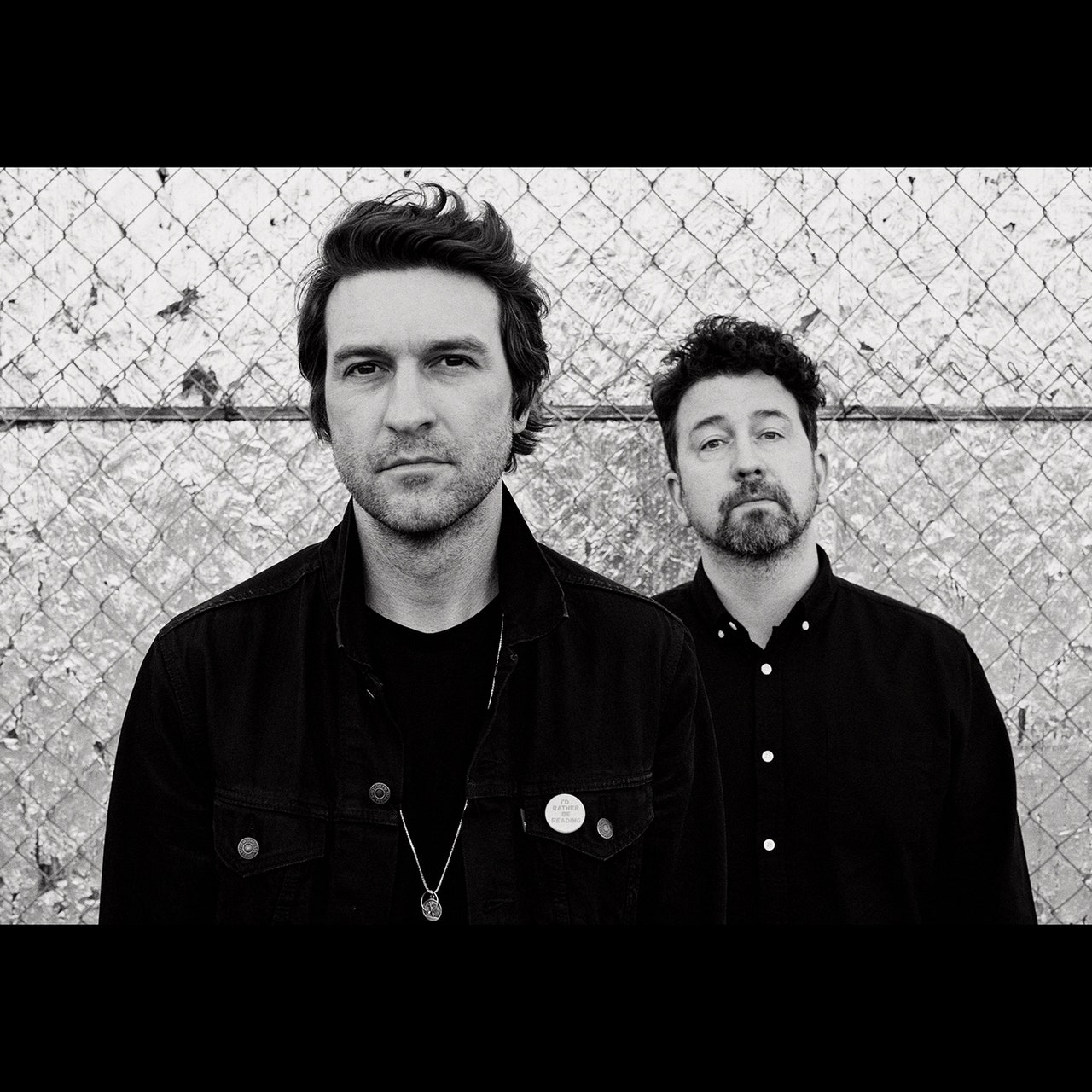

In the seven years since 2017’s Near to the Wild Heart of Life, at least one of the boys (vocalist and guitarist Brian King) finally left town (Vancouver, BC), to become a man: married, one year sober, living in Michigan, with a baby on the way. This has, unsurprisingly, posed a series of existential threats for the band: How can they reproduce the lightning-in-a-bottle enthusiasm they created when King recorded in the same room as drummer and backing vocalist David Prowse? How can they sing about “bikini island” and wanting to “French kiss some French girls” when they have wives back at home? How can they keep lamenting about how “nothing changes,” when more accurately, nothing has been the same for them in over a decade? They had already begun to wrestle with these thoughts on their prior album, replacing their local watering hole with lyrics about every party city across the USA.