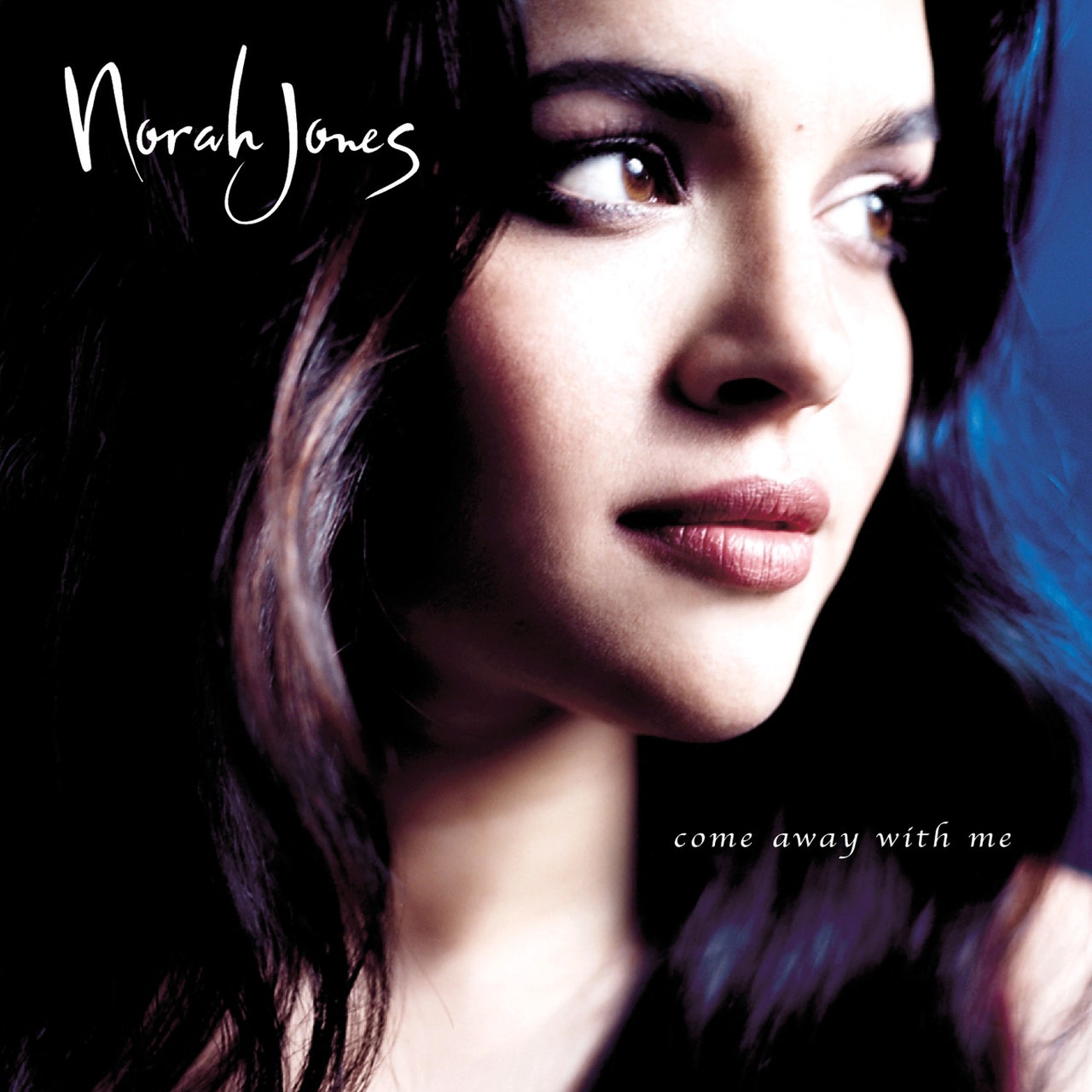

Norah Jones, cradling an armful of gold, spoke sheepishly at the 2003 Grammys. The 23-year-old singer-songwriter had just swept the lauded Big Four categories for her debut album, Come Away With Me; over the previous year, her gentle rasp of a voice floated out of seemingly every Starbucks, wine tasting room, and parents’ CD changer. Yet the nascent star, with her fresh-faced appearance and bounty of dark curls, was visibly stunned by her own success. She could scarcely believe that one of her idols, Aretha Franklin, was sitting front row that night as she performed the album’s doe-eyed lead single, “Don’t Know Why.” Standing so close to a legend she’d grown up listening to sent Jones into a tailspin. “I didn’t expect this,” she said of her winnings that night, “nor did I need it.”

Jones was partly right. Come Away With Me had already sold 4 million copies, riding high off the breezy, inescapable “Don’t Know Why,” not to mention an unprecedented marketing push from vaunted jazz label Blue Note. Since the record’s release the previous February, she had sold more records than any other artist in the label’s storied history, including titans like Thelonious Monk and Miles Davis. But Jones’ subdued response to her swift acclaim was genuine. At one point, a rumor arose that she had asked Blue Note boss Bruce Lundvall if they could pull the record from shops to prevent listener burnout. No such luck: The laid-back, preternaturally beautiful Come Away With Me, still Jones’ best album despite its sleepy reputation, struck a singular chord with both the music industry and general public, going on to sell an eye-watering 27 million copies to date.

Jones was born in New York City to Sue Jones, an Oklahoma-born nurse and former concert producer, and the celebrated Indian sitar player Ravi Shankar. The pair’s relationship blossomed in the late 1970s, but they split after nine years, and Sue moved with 4-year-old Norah to Grapevine, Texas, a small town northwest of Dallas; Shankar and the family wouldn’t reconcile until Norah was 18. (“All families have their complicated corners,” she said when looking back at the strained relationship in 2020, eight years after Shankar’s death. “It took us all some time to feel comfortable with each other.”) Jones credited her own early interest in music to her mother’s vast record collection, a library that spanned Ray Charles to Pavarotti. Billie Holiday became an early north star; Jones would play her favorite songs from her mother’s eight-disc Holiday compilation on repeat, especially the ambrosial “You Go to My Head.”