The first records to carry the Basic Channel name wore it quietly, stretching and distorting the text across each record’s center label, and rendering it fainter with each release. Was Basic Channel an artist’s name? Placed alongside titles like “Phylyps Trak” and “Quadrant Dub,” the early records seemed to imply as much, even as others, like “Enforcement” and “Inversion,” were credited to someone called Cyrus. Perhaps, then, Basic Channel was a record label. But who was Cyrus? And who was responsible for pressing these elegant 12″ singles?

With visual design that nodded to conceptual art’s brief fascination with Xerox machines during the 1960s, they made a clean break with the futuristic features of Detroit techno, which was just beginning to settle into orthodoxy by the early 1990s. Wherever they came from and whoever was behind them, nothing else sounded quite like Basic Channel.

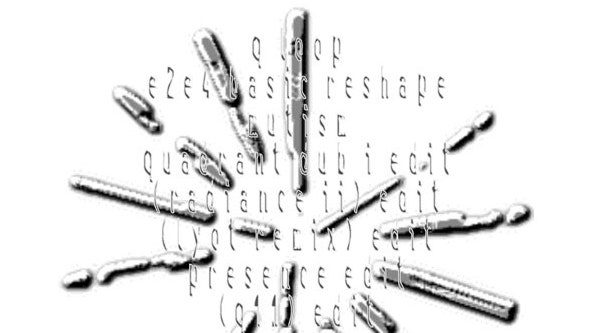

The project moved quickly, producing nine 12″ singles for the label between 1993 and 1994. The records were austere yet intricately constructed, using atmospheric synths and studio effects to create astoundingly dense structures that revealed new patterns with each listen. The duo’s first single, 1993’s “Enforcement,” accosts listeners with a brutal synth loop that repeats, with slight variations, for the duration of the 13-minute track. Yet those subtle changes make all the difference; muffled hi-hats and hard-panned synth pulses peek through at steady intervals, colliding with the original synth sequence to reveal new contours as the track progresses. The approach borrows as much from Manuel Göttsching’s motorik E2-E4 as it does from the dizzying phase music of minimalist pioneer Steve Reich, churning forward at a relentless pace without inducing fatigue.

The pair would ultimately turn away from thundering techno, shifting their focus to subtle textures. But the single contains a template for much of what would follow, introducing mixing techniques that prioritize space, as well as a careful focus on process, that Mark Ernestus and Moritz von Oswald—the press-shy individuals eventually revealed as the artists behind the alias—would carry throughout their careers. The track, like others including “Q1.1/I” and “Octagon,” was heavily inspired by Detroit techno, taking influence from Juan Atkins, Jeff Mills, Robert Hood, and labels like Metroplex and Underground Resistance. This scene was the blueprint from which Basic Channel would establish—and perfect—a completely new sound of their own. To purists both then—a period when techno’s sprawling nightlife network was just beginning to coalesce against the backdrop of German reunification—and now, dub techno begins and ends with Basic Channel, whose 1995 compilation BCD remains the genre’s defining document.