Chris Cohen writes songs so gentle and sweet they seem to practically nuzzle up against you, but he hasn’t always intended to be a steward of comfort. “I think that there’s something in my music that people misinterpret as like, contentment or being chill,” he told Flaunt in 2020, lamenting the times he’s noticed his laid-back bedroom pop crop up as background music in restaurants or at Urban Outfitters. “It might be something that I’m not succeeding at as a musician that makes people think that I think the world is fine and we should just feel good,” he said. “That’s like, the last thing that I want people to get from my music.”

Cohen’s curse may just be that he’s too adept at crafting gorgeous, heavenly little songs. If there’s one throughline between the various projects he’s been a part of—be it Deerhoof, Weyes Blood, Ariel Pink’s Haunted Graffiti, or the Curtains—it’s this sense of him tapping out cracks in the edges of soft pop without ever letting it shatter. “Damage,” the opening track off Paint a Room (his first new album in five years) puts this dichotomy front and center: As Cohen, dismayed, sings about how abuses of power manifest in society, a summery bed of horns courtesy of Jeff Parker envelops his dread in a pastoral calm. “Somebody’s love was shot down again,” he coos, just moments before a smooth saxophone solo swirls into view.

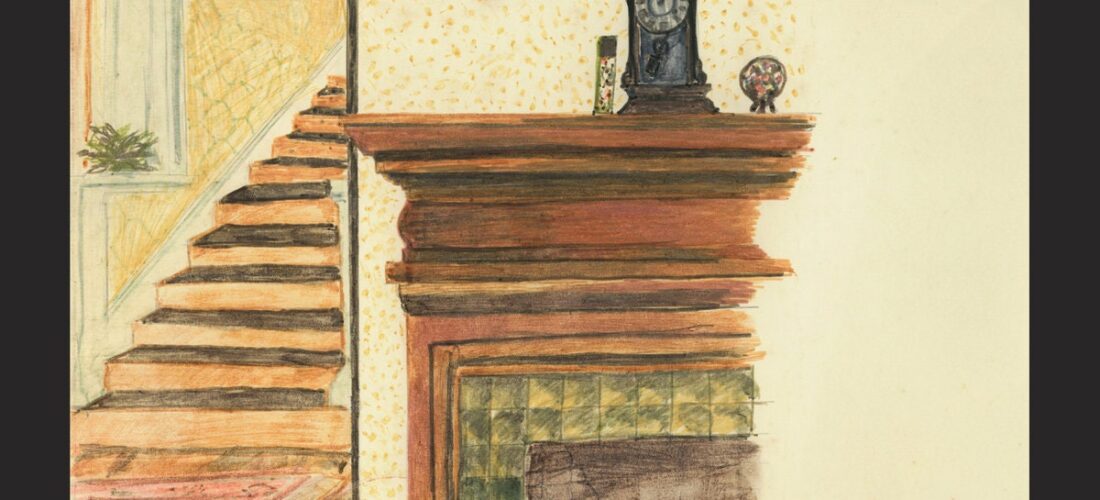

Paint a Room is full of these types of frozen-in-time vignettes, as Cohen’s intimate songwriting comes to life in blossoming arrangements seemingly plucked straight out of a vintage California bachelor pad. Inspired by Uruguayan and Brazilian artists like Eduardo Mateo and Milton Nascimento, who pushed their folk pop to proggy, boundless new places in the ’70s and ’80s, Cohen lines his songs with flutes, congas, and Clavinets that instill a psychedelically tropical lilt. At times, the subtly pretty haze can threaten to dissipate into thin air, but its highs demonstrate why Cohen remains one of indie rock’s most quietly wondrous songwriters.

Cohen’s melodies convey everything his songs need completely on their own (he typically plots out all his chords and phrasings well in advance of figuring out what to actually say). His hooks can feel so simple and intuitive that it’s as if they’ve always been there: The central piano motif in “Dog’s Face” materializes as gracefully as a mist unspooling over the Bay, before a lightly dissonant guitar riff begins to pulse like distant thunder. The ghostly keyboard riff in “Randy’s Chimes” creeps around as if it were solving a mystery, while “Physical Address” cruises on a playful bossa-nova groove that glides up and down like a kid riding an elevator. When Cohen does attempt to say something more concrete with his lyrics, his concerns tend toward searching for hope in the modern day. On the radiant “Sunever,” he speaks to a transgender child about the future: “Up and up you climb, soon you’ll leave us far behind,” he murmurs tenderly, promising them that “you’re gonna find a way” and letting a joyous fiddle paint the path.