You’d think that one of the greatest vocalists of all time might have some notes for rising musicians. But as a judge on the 2012 reality singing competition Sur Kshetra, famed Pakistani Sufi singer Abida Parveen was often exceedingly neutral. When asked in an interview why she avoids sharing criticism despite being appointed as a judge, she responded with her typical wisdom: “Because it’s music, not war.” The journalist interviewing her followed up, asking who she hoped would win the competition. “I pray Allah makes a good decision. That’s all.”

Parveen’s humility and diplomacy are almost comical given her position as one of the most famous and influential musicians in South Asian history. When she was 5, her father chose her over her brothers to become his successor in their family practice of Sufi singing, and by the age of 23, she was named the official singer of Radio Pakistan, the national public broadcaster for radio in the country. Now 70 years old, Parveen, who is often referred to as “the queen of Sufi music,” has released over a hundred albums, received the Nishan-e-Imtiaz—Pakistan’s highest civilian award—and is credited with helping popularize Sufi music and culture among young people in South Asia and around the world.

Parveen’s modesty despite her immense success is part of her religion. She makes music in the tradition of Sufism, a mystical, philosophical expression of Islam that began in the 10th century. Sufism prioritizes spiritual purification, a divine, intoxicating connection with God, and a sense of humility that comes from prioritizing that connection above all earthly desires. In interviews, Parveen often deemphasizes her importance as a person, instead positioning her performances as a means for communing with God. “The truth doesn’t need to be told,” she said in an interview in 2001. “It can only be experienced. Remember, I’m not performing. He is singing through me. It is His song, and it sings by itself.”

Sufism also specifically deprioritizes the role of the singer in music-making. The Sufi practice of sama’—listening to music with the intention of achieving closeness to God—instead privileges the listener. The concept of sama’ has inspired artistic movements across the globe from Turkey’s whirling dervishes to Morocco’s Gnaoua music, which has had an outsized influence on jazz greats in the West like Ornette Coleman and Pharoah Sanders, to name just a couple.

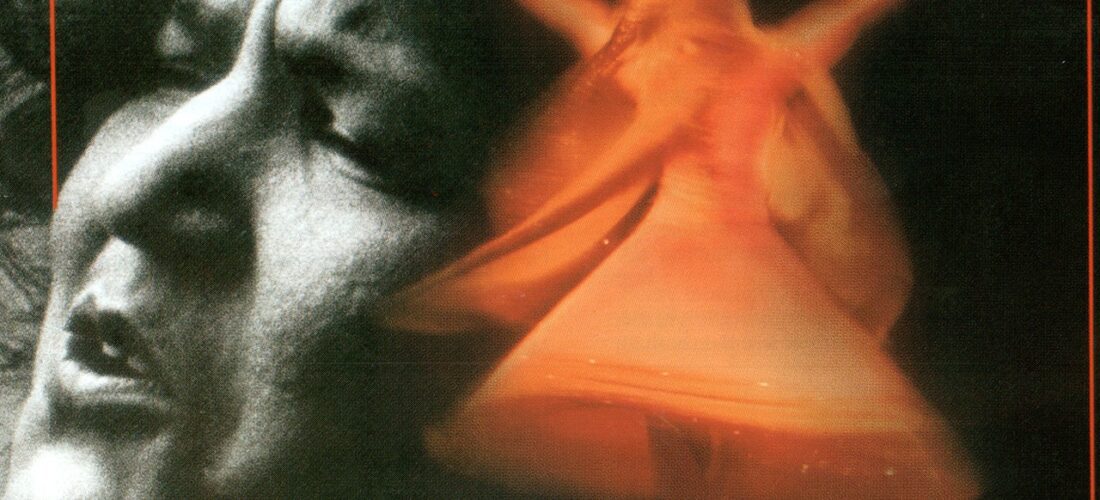

On stage, when Parveen channels the greatness of God, she transforms completely. She sometimes hallucinates while on stage, or brings the audience to tears by singing just a few notes. Nowhere is her singular vocal talent clearer than on her excellent 2000 album Raqs-e-Bismil. The album title translates to “Dance of the Wounded,” and on the record, Parveen conveys burning desire and yearning for God through the subtleties of her singing: the poise with which she delivers a single note, the husky, smoldering tone of her voice, her interplay between precision and fervor. She’s often compared to Nina Simone, whose shows have been described as “having the aura of sacramental rites.” The two artists sing with such dynamism and heart that when you listen to them, you feel transported beyond the limitations of your body and individual perceptions and into a spiritual realm of infinite possibility.