In a photograph snapped on the evening of April 23, 1961, a line of disembodied hands reach out to grasp for Judy Garland onstage at Carnegie Hall. They belonged to a group of men whose allegiance to the star was as passionate as it was fraught; as bound up in their identification with her strength and humor as with the many troubles of her life. Their cohort could only be spoken about in code, and in time, a whole vocabulary emerged to describe them: friends of Dorothy, the boys in the band, Best Judys. To journalists and outsiders they were objects of amusement, if not outright scorn: “the boys in tight trousers,” “ever-present bluebirds,” or as one writer bluntly called them, “a flutter of fags.”

What’s most striking about this image is Garland’s responsiveness to the people connected to those flailing limbs. Her eyes are cast downward, reciprocating their gaze, engaging them as individuals rather than an undifferentiated mass. Most accounts of that evening are of a restless and animated audience, leaping out of their seats and swarming the footlights to be closer to the singer. According to one review, the fervor was so intense “you could not tell whether the crowd was clapping, shouting, screaming, laughing, or crying. The sound suddenly had no character. It was just an expression of total approval and acceptance.”

“It was, even by the strictest definition, perfect,” Gerald Clarke, Garland’s biographer, wrote of her series of performances at the storied New York concert hall. But strict perfection is at odds with Garland’s enduring appeal. The expressiveness of her voice outpaced its technical merits. Her genius was using a flawed human instrument to communicate something far more complicated than a lovely song sung straight. She approached show tunes and pop standards with such unguarded emotion that they came to seem disarmingly personal, no matter how well-known or widely performed. Despite her music’s theatricality, the scrim separating the person from the performer was unusually thin: the draw of a Garland concert had as much to do with her glamorous presence as her unbridled singing.

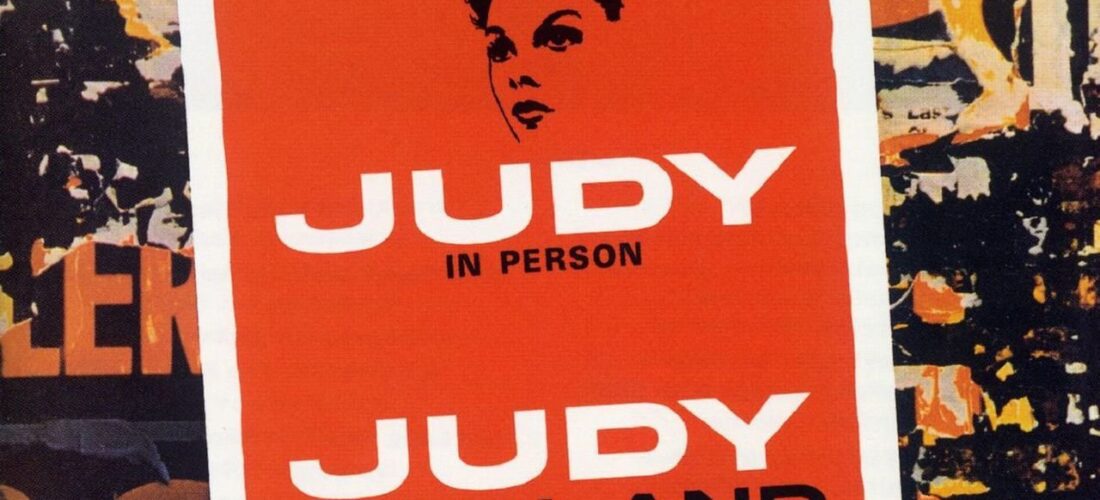

The mystique of Carnegie Hall was only enhanced by the success of its recording. Judy at Carnegie Hall spent 95 weeks on the charts and 13 of them at the No. 1 spot. It won several top awards at the 1962 Grammy Awards, including Album of the Year, the first ever awarded to a woman. It was a record that lived up to the hyperbole of its liner notes and soon was widely known as “the greatest night in show business history.” After a sometimes rocky 1950s, it once again reaffirmed the star power Garland had always possessed, marking the moment when the singer and her audience were in perfect sync with one another; when the peak of her powers as an artist was met with the kind of sustained and unconditional recognition she’d always sought.