Remembering Bill Withers’s Singular Voice

I spent most of my 20s toiling away in supermarkets and minor chain department stores, making just enough money to get to the next week in one piece. (My heart goes out to grocery store employees in hectic public-facing positions during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is draining, often thankless work on a good day; if their work is essential, so are their needs.) Music got me through the endless days. The side effect of a three-year stint pacing the floor in a discount store was a working knowledge of ’70s and ’80s singer-songwriter classics. One of the crown jewels of the playlist was Bill Withers’s “Lovely Day,” a song about clinging to the tiny pleasures that make life bearable, the rare feel-good tune that acknowledges there’s a lot to feel less-than-good about — a lifeline at a shit job. I used to try to match the breathing on the high note in the song’s closing chorus, where the singer holds the word “day” for 20 seconds. It’s not very hard to exhale for that long, but keeping that note from wobbling is another story.

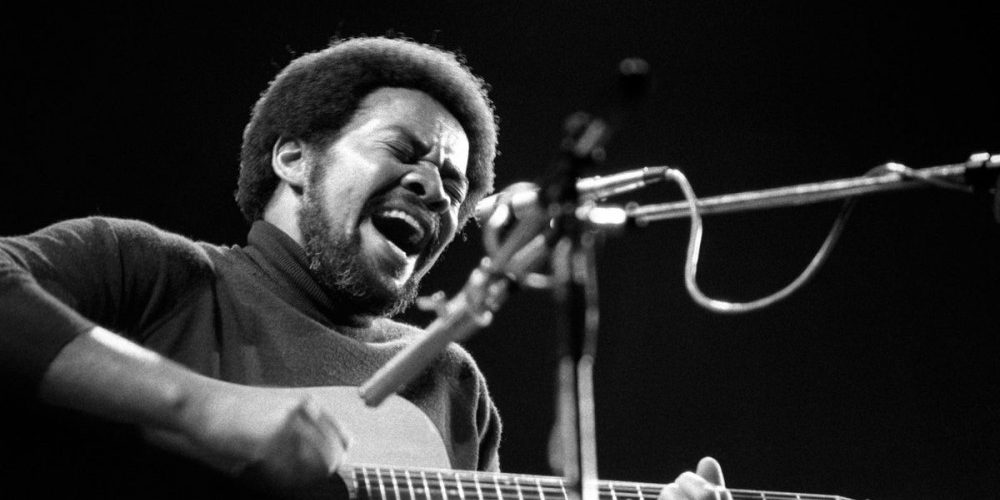

Bill Withers, who died last week at 81 of heart complications, wasn’t a showy vocalist. His voice ran coarser than the buttery tones of titans of soul like Marvin Gaye; less hot and mercurial than guys like Teddy Pendergrass, whose songs stewed to sweaty climaxes, like rice pots boiling over or heart rates shooting up in a moment of passion. Bill Withers was a straight shooter as a singer, sort of like a church pastor in the sense that really, he was just talking to you, but sometimes the music would catch him unawares, and sturdy blue notes would deliver his message for him when words failed. “Grandma’s Hands” memorializes the “old-time religion,” emulating a southern church hymn’s rootsy refrains as it celebrates a wise matriarch’s boundless faith. The two-word ad-lib in “Ain’t No Sunshine,” a placeholder vocal Withers had intended to replace with a written verse until he was coaxed to let it rock, is one of many moments in the West Virginia singer’s catalogue where soulful scatting packs as much of a punch as precise writing. (See also: “In My Heart,” a song short on words but very long on breathless melisma, which builds to a climactic howl, foreshadowing the lung workout of “Lovely Day.”)

You can almost hear Bill Withers’s life story in the stately, acoustic soul songs of his ’70s heyday. He spent his formative years as a Navy man and later as a factory worker, quietly squirreling away songs, before catching a break in getting a demo to Clarence Avant, also known as the Black Godfather, who ran the Los Angeles indie Sussex Records. (Withers once noted that the cover for his 1971 debut, Just As I Am, was shot on lunch break at the factory, a detail that makes the title all the more fitting.) The Sussex material is unusually mature and reserved for a new(ish) artist. This is a byproduct of years of writing and hard living. On 1973’s Live at Carnegie Hall, the Vietnam War anthem “I Can’t Write Left-Handed” is introduced with a monologue about arriving at the song’s political awareness, after years of service and seeing the effects of the war on soldiers firsthand. The gravelly but pitch-perfect delivery reflects the no-nonsense outrage of a man on the street who’s just seen too much. “Use Me,” from 1972’s Still Bill, boils to a froth over a reflexive lyric about manipulative people that works as a song about love going sour and a negative reaction to sudden fame.

“Use Me” was prescient: When Clarence Avant’s Sussex imprint folded, Withers jumped over to Columbia Records, where his music lost a little of its purity amid increasingly fussy arrangements that seemed to strive for the success of lush mid-’70s chart hits like Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes’ “Wake Up Everybody” and the O’Jays’ “Love Train.” It didn’t work, but this was through no fault of the artist, as the lasting appreciation of “Lovely Day” and the Grover Washington Jr. collab “Just the Two of Us” would prove near the end of a career cut short when Withers got sick of fighting the label for control of his music and gave up singing entirely. All Bill Withers ever needed was a team that trusted him enough to get out of the way. Running back deep cuts like “Moanin’ and Groanin’,” a short, skeletal guitar-and-drums vamp that floats almost solely on the singer’s jumpy, lustful lead and backing vocals, you wish he had the chance.