Hüsker Dü’s “Flip Your Wig” isn’t so much a song as a status update from a world before social media. The excitable opening track from the namesake 1985 album is an on-the-ground dispatch from the eye of the hype storm that engulfed the Minneapolis trio as they transitioned from SST hardcore antagonists to Warner Brothers-backed alt-rock trailblazers. The song marked the rare occasion where both principal songwriters—guitarist/vocalist Bob Mould and singing drummer Grant Hart—shared lead vocals, despite their notoriously thorny relationship. But even at their most optimistic, their lyrics dripped with cynicism. “Sunday section gave us a mention/Grandma’s freakin’ out over the attention,” Hart sings, excited that his days of sleeping on floors are coming to an end, yet wary of the hangers-on and opportunists that emerge from the woodwork when you’re crowned the next big thing. “Long distance on the other end/Says I need them for a friend/No matter what I choose/I’m the one they wanna use.”

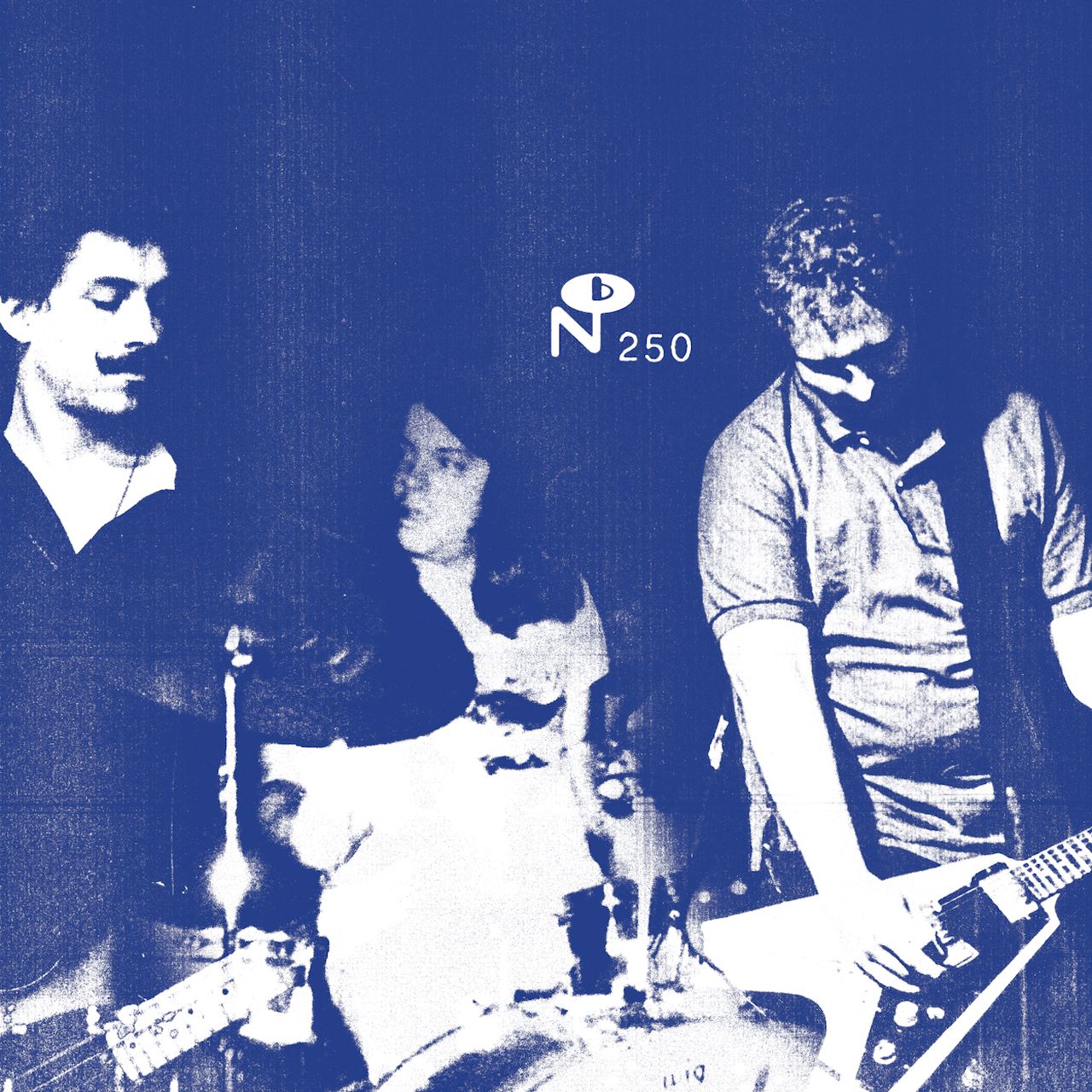

If “Flip Your Wig” provides a two-and-a-half-minute snapshot of what it was like to be in Hüsker Dü in 1985, a new Numero Group box set gives us the director’s cut view of a band that, at the time, seemed unstoppable—a term that applies equally to their relentless onstage attack, their prodigious rate of musical output, and the great strides they made as songwriters with each new release. Between the summer of 1984 and winter of 1987, Hüsker Dü released five albums that perfected the balance of melody and noise that would define indie rock for decades to come. 1985: The Miracle Year drops us right in the middle of this phenomenally productive stretch with two discs of live material that constitute not just a generous gesture of fan service, but a crucial act of restorative justice for a band whose legacy has long been ill served by their studio albums.